City Room 101

From Japan to Boston to Singapore and beyond, the concept is a recurring ingredient in urban buildings that negotiate public and private interests. What exactly is it?

~4,200 words, a twenty-one-minute read

My first essay on city rooms can be read here. Early subscribers of PinP saw this in April. This follow-up piece on the topic is admittedly less tightly-knit than the first; very much a working document. Substack feels like a good platform for such things.

I suppose I should warn you: this is an absolute unit of a post.

In it, I’ve wrestled with an attempt to formalize a constellation of thoughts that developed from subsequent observations and from feedback on the original Docomomo essay. I got very helpful responses after sharing that around, which came in a variety of forms including thoughtful emails from former professors and even some comments on Instagram that popped up after Harvard featured me there. It’s a brave new world we’re in, feedbackwise, isn’t it.

So since April, I’ve continued to work through the issues but until now this existed only in a pile of notebooks, the crevices of my memory/imagination (are those two sides of the same coin?), and in random epiphanies that emerged when writing about city room cousins: covered streets and covered sidewalks.

1. The basis for further development of the city room concept:

Following my working essay “Singapore’s City Rooms”, I received helpful and instructive feedback that largely centered around two lines of questioning:

What really makes a city room a city room? The cases described seem to be about spaces that — to the lay person — are basically shopping mall atriums.

What are the relevant rules and/or policy frameworks that regulate public use and access of city rooms?

Answering these questions is best done with a clear definition of what city rooms are. The rest of this post will revolve around attempt to form such a definition.

2. A quick note on the place of “city room” in the English lexicon

There is a dictionary definition of city room. It may not be what you expect. Nor is it what I am writing about. Here’s Webster’s:

city room (noun): the department where local news is handled in a newspaper editorial office

For its part, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) does not list the term at all. It does have a word for what Webster’s dictionary described, but it’s “city desk: the department in a city newspaper office which deals with local news”. Regardless, the city room that I am/have discussed is not officially part of the English lexicon.

One goal I have is to formalize this other meaning of the term: the one that refers to the type of urban space that I am investigating here in Singapore. As I explain below, Singapore is an epicenter of sorts for the concept. If nothing else emerges from this little adventure abroad, the increased popularization of the “city room” seems like a noble pursuit. I’m trying to do it without hammering the term with hashtags, too.

Can “city room” make a debut in the Oxford English Dictionary? Well, we all need something to get us out of bed in the morning. Plus, the terms “shopping mall”, “boardwalk”, “living room”, and “bus stop” made it in there at some identifiable point in time. And I’m certain humanity is not done making new compounds.

3. The Singaporean government’s definition of a city room, according to the Urban Renewal Authority (URA)

A 2016 document published by the URA on Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS) defines three types of space: city rooms, plazas, and urban parks. It defines city rooms as:

Covered public spaces located at the 1st storey of the building. They function as spaces for respite within the dense urban built environment.

The conflation of city rooms and POPS had not been explicitly formalized by Singapore’s primary planning agency until this time. It’s interesting to see that with this relatively recent categorization, subsequent projects under this framework are now being completed and promoted as such. Take, for example, CapitaSprings, which explicitly markets its covered ground floor space as a city room (going as far as to capitalize the C and the R!):

Along with the redevelopment, part of Market Street will be converted into a public park, blending seamlessly into the City Room at CapitaSpring. If you're looking for a quiet spot to relax in between meetings - pick up a coffee on Level 1 and have a seat on one of the benches. Community events like fitness sessions and lunchtime performances will also be held at the City Room. (Capitaland Website)

And in an unmistakable copy of a tactic used in New York City (the de facto intellectual birthplace of POPS) the City Room at CapitaSpring even comes with signage, presumably in an effort to ensure the public knows the space is public and perhaps so the (private) developer also is reminded that the public knows the space is public.

See also: extensive guidelines on POPS in general as defined by the URA on their website, here. There are clear similarities to the POPS regulations in New York City.

If (and as I hope they are) city rooms are worth considering from design and planning standpoint in non-Singaporean contexts, the URA’s definition is worth expanding on in order to provide greater clarity to outsiders interested in the subject.

But first,

4. The obvious similarities between city rooms and POPS deserves some attention.

Across American cities and other global contexts, the details of how privately owned public spaces are conceived, regulated, and maintained may differ by locale. Real estate is, after all, local. But for the purposes of this piece, I’ll draw on the influential work of Harvard University professor Jerold Kayden. Around the year 2000, Kayden and a team of researchers did extensive observation and analysis of POPS in New York City. The work culminated in a book, Privately Owned Public Space, The New York City Experience, and an interactive website.

(Incidentally, the website in particular is a quite comprehensive and refreshingly up to date: website visitors are invited to send a “comment on a POPS”, and a “News and Announcements” feed is actively updated to keep track of all things POPS, including whether developers are sticking to their promise of providing space that is truly public, and whether the city is doing their part to properly enforce the law.)

In general, POPS are the result of a negotiation between public and private stakeholders that provides concessions to developers (i.e. increased building height) in exchange for those developers building and maintaining small public spaces on their land or in their buildings. In New York, this exchange was formalized in the zoning code in the 60’s. Since then, hundreds of POPS have been built over the years, especially in dense, high-land value areas like downtown and mid-town Manhattan.

Kayden and his research team classified 503 POPS on qualitative spectrum of sorts, classifying each as (from best to worst): Destination, Neighborhood, Hiatus, Circulation, or Marginal.

More could be discussed here, but the punchline is that according to the POPS database, the covered plaza space at IBM plaza (pictured above) was designated as a space that “has garnered near universal recognition as New York City’s peerless privately owned public space, a tree-filled conservatory and public living room rolled into one” (text from profile by Jerold Kayden).

Based on my working definition in point #7 below, IBM plaza appears to fit the definition of a city room. It follows, then, that city rooms may in fact sit at the top of the POPS hierarchy, the apex of the collision of public and private forces at its highest quality and more vibrant civic expression.

Notably, I am taking the stance here that city rooms are more appropriately defined in architectural terms than policy terms. I’m arguing simply that the words “city” and “room” make this solidly and unmistakably an architectural concept (although I am no linguist, and am probably biased in associating words with architectural meanings, and this probably an easier argument to make with the word “room” than it is for the word “city”.) “Privately owned public spaces” is a phrase with intrinsic policy and regulatory implications, and of course in places like New York City, the term has specific legal meanings. City rooms do not (yet).

Certainly, the Singaporean context contributes to my judgement on this. As I point out below, the fact that city rooms don’t come with a one-size-fits-all policy framework is in large part because they exist in a variety of ownership structures. In Singapore, city rooms (at least if defined in the way that I am defining them) can be found in publicly owned public spaces, privately owned public spaces, and privately owned private spaces.

So, there is something of a Venn diagram here:

And to continue in the Venn diagram mode, there is an addition that may provide further clarity about the other similarity to shopping malls.

Speaking of the Singaporean context,

5. A brief review of city rooms (not the newspaper kind), in practice:

The concept appears to have originated around 1970 in a small publication by Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki called The Theory of Group Form. Barring further insight from Maki himself, one is left to conclude that the idea was creatively dreamt up by him and/or his colleagues in the soup of ideas about 60’s-era Metabolist infrastructural megaprojects that he became well known for. Maki did not say much about city rooms specifically, but provided an illustration along with a brief description in a section called “Communication through Public Spaces”:

The most important factor in a group form is treatment of mediating public spaces. In 1964, while teaching a course in urban design to a group of selected Harvard students, I engaged in research on a Boston movement study program. In that study, I attempted to show that creating organic public spaces centering on traffic focal points throughout the city would significantly effect the rehabilitation of urban centers. Although the details of the program are to be found in Movement Systems in the City (Harvard University, 1966), I can briefly explain the gist of the idea as follows. First in terms of urban design, we must create, city corridors, city rooms, and transportation exchanges in strategic points in the city; and second we must require that these new focal points become urban energy generators. The architect does not concern himself with the ways city corridors and rooms will be used. Instead, he creates unspecified spaces that stimulate spontaneous events. We applied the same ideas to the stations and corridors at the Rissho campus and to the public space at the Daikanyama apartments. In other words, we create a stage in the city. This space itself becomes a communications media, but unfortunately because too many architects forget this simple fact, similar ideas often degenerate into nothing but a kind of formal play with space. (Maki, 3-4)

It’s almost tempting to point out the contradictions in that blurb: on the one hand, the architect is not to be concerned with use, yet somehow those spaces are to become urban energy generators. If the space is to be used for spontaneous events, doesn’t that require one to be concerned with that use? But the important point, I suppose, is that these were spaces theorized to be unmistakably of the public realm. But, as we will see, this is one aspect where theory and reality diverge.

The city room concept is known to have influenced early Singaporean architects like William Lim who attempted to implement the idea in experimental, strata-title mixed-use projects like People’s Park Complex. Apparently during construction, Maki visits and famously says “we theorized it, and you people are getting it built”, according to Lim in his 1990 book, Cities for People. As I point out in the article linked above, People’s Park Complex was — somewhat uniquely for Singapore — a completely private development, land included. It’s not clear if Maki was perturbed by this. Regardless, Singapore’s continued experiments with strata malls such as Golden Mile Complex solidify the tropical nation’s status as something of an incubator of the city room “theory” as manifest in built form. This is reinforced when Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas describes the Maki/Lim dynamic in his 1995 essay, “Singapore Songlines”.

Following the theorization of the late 60’s, early implementation in the early 70’s, and the brief renewed interest by Koolhaas in the 90’s, the concept does not appear to have gained much traction in the architectural lexicon. This is either surprising or not, depending on ones views of the strange, insular vocabulary that academically inclined architects tend to adopt (see ArchDaily: “150 Weird Words That Only Architects Use”).

Koolhaas’s architecture firm OMA occasionally uses the term to describe spaces in their designs. For example, see the WA Museum Boola Bardip in Australia.

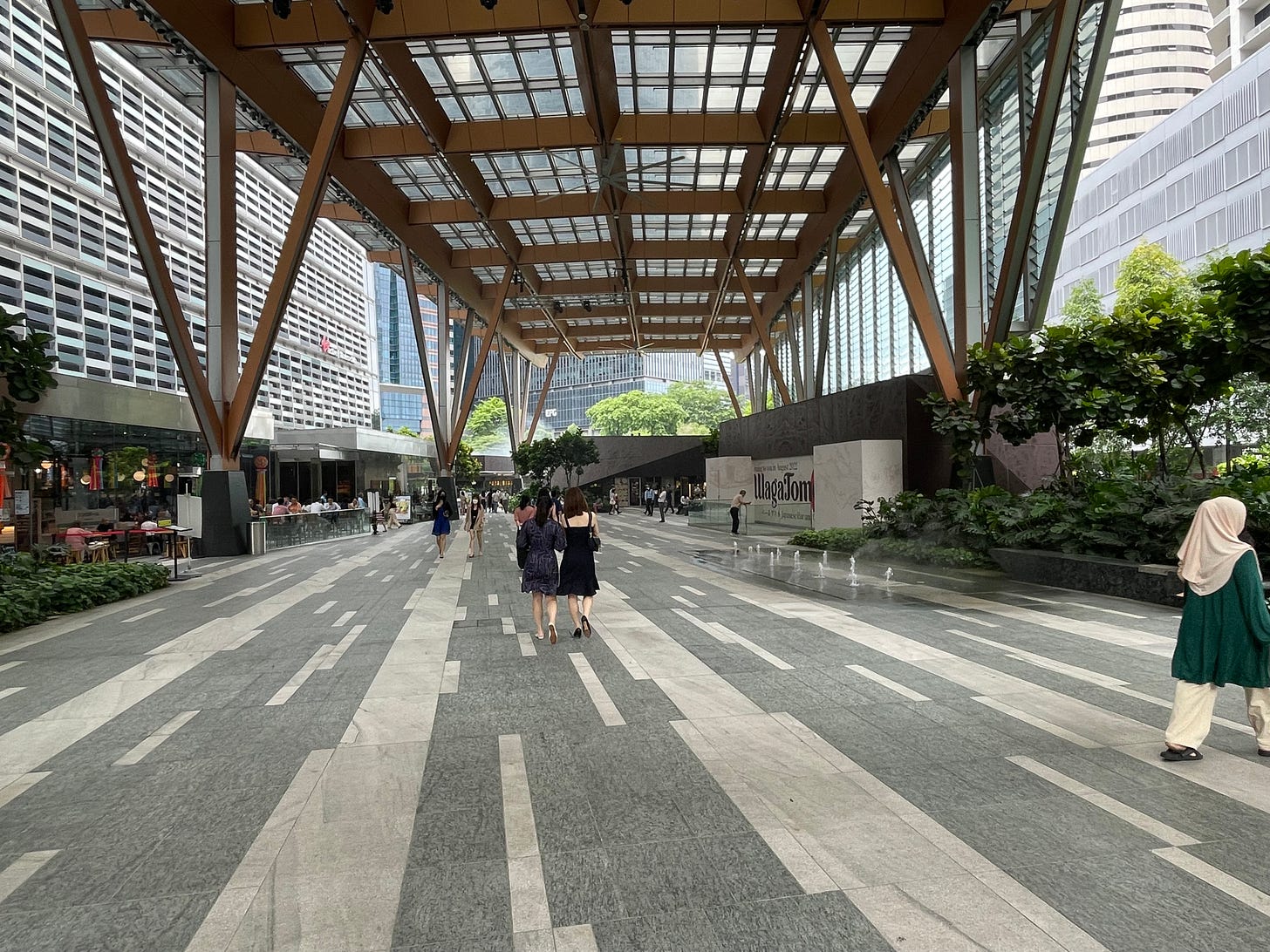

But around 2015, the term appears to be making a comeback of sorts in Singapore, perhaps best exemplified by the URA document listed above, and in the marketing materials by developers of high-profile projects. For example, see the POPS-like space at the Guoco Tower city room (pictured below).

6. Some incomplete notes on Singapore’s peculiarities:

Singapore is a unique country with a unique model of governance and a unique constitution. I will not do justice to the complexity of this fact here. Briefly, as far as public space is concerned, the most obvious implication might be best outlined by Limin Hee, who wrote the comprehensive dissertation: Constructing Singapore Public Space. In it, she outlines a Singaporean model of Public Space that is markedly different from western notions of public space which tend, at least in some academic circles, to be “concomitant with democratic political practice” (Hee, 197).

Take, for example, the fact that in Singapore, public demonstrations are illegal under most circumstances. (There are exceptions; I am not going to delve into this here.) In practical terms, the implication for the visiting researcher (me) is that public space in Singapore may be most appropriately studied with regards to functional, utilitarian aspects of ordinary, everyday life, rather than the more abstract notions of public space as some kind of embodiment of ideological contestations and western democratic ideals.

With that in mind, the following is based on the investigations articulated in the previous points, as well on subjective observations of various city rooms by me.

7. My working definition of a city room:

A city room is a type of finite urban space that is:

Enclosed

Multi-story

Within or directly adjacent to a single building

Smaller than a city block but bigger than a lobby

Pedestrian accessible and inhabited

Open to the public during working hours or longer

And which:

At minimum, contains one commercial and one non-commercial function.

Supports temporary exhibition-style events throughout the year.

Each of these points is surely debatable, as is the nature of the definition: four of these points refer to spatial attributes, and four refer more to functional attributes. Again, I’m arguing that “city” and “room” refer respectively to functional and spatial concepts.

The list is — as far as I can tell so far — the bare minimum requirements for a space to obtain the noble “city room” designation. That is to say, start to remove these properties and a space quickly ceases to become a city room. Here is a brief, in progress elaboration on each of the eight points:

Enclosed: An unenclosed space is no longer a room. A city room is not a city room if it is not a room! As a rough working definition, enclosures requires 1) a floor 2) a roof or canopy 3) something on at least two of the sides.

(Philosophers could debate what “enclosure” really means for hours, but let’s just say for practical purposes that it means at least four out of six sides are reasonably enclosed by something.

The city room at Guoco Tower, enclosed on the sides by F&B outlets as well as the office tower lobby beyond (to the left), and of course enclosed above by a translucent canopy. Incidentally, this is a case where the developer explicitly advertises the space as a “city room”…see here. Multi-story: A single story space at the scale of a city room would not have the proper proportions of a room. A civic scale in the vertical direction becomes naturally necessary for the “city” qualifier.

Within or directly adjacent to a single building: It’s difficult to imagine one room as a part of two separate buildings. City rooms, like rooms, are singular in nature. A canopy covered street, for example, might feel like a city room but is probably better described as a city street or a city corridor, as it is defined by adjacencies with multiple properties.

Smaller than a city block but bigger than a lobby: Related to the last point, the singleness of the room logically lends itself to the confines of a city block. That’s the upper limit. An enclosed space larger than one city block approaches something like a grand exhibition hall or stadium type space: not very room-like. Then there is the lower limit. In dense urban environments, the biggest indoor unit of space at ground level — other than mall atriums (more on that later) — are probably office lobbies. City rooms must be bigger since they are more public and more diverse in function, and therefore necessarily larger to accommodate more people and uses.

Pedestrian accessible and inhabited: Rooms are, after all, inhabited by people, who access them by walking (i.e. not driving) into them. Pedestrian accessibility and inhabitability refers to the connectedness of the space to city pedestrian networks like sidewalks and other urban public spaces. For this reason, it’s nearly impossible for a city room to exist at any other level other than ground level although in theory they could exist at other datums served by a robust network of elevators and escalators. As a practical matter, an urban space not accessible to pedestrians is alternatively accessible to vehicles, at which the space is either a road or a parking lot. The point may seem obvious, but one forgets that “public space” often includes vehicular spaces, so the distinction is meaningful.

Open to the public during working hours or longer: This can quickly slip into the endless debate about whether shopping malls are public space or not. For practical purposes, these are spaces that must be reasonably open to the public during reasonable hours. There is a noble temptation to claim that only spaces that are free and open to the public 24/7 are truly public, however it strikes me as impractical to claim a space contributes no civic benefit simply because it’s not open at 3:30am. It may be sufficient for practical spaces to simply be open at practical times.

At the very minimum, contains one commercial and one non-commercial function: My hope is that this resolves the crux of the rebuttal that these spaces are no different than shopping malls.

There are two points to discuss here. The first is about what a “function” actually is — if a civic event only happens one day the entire year, does that count? Perhaps “city room” is a temporal designation. I as I wrote in the first essay, People’s Park Complex was originally used for a great deal of civic programming, but is no longer. Could we then say it WAS a city room, but is no longer worthy of the title?

The second is what “non-commercial” really means. Would recreational programs count? That would make a place like the Funan Mall atrium, with its climbing wall and interior bicycle loop, a city room. But it’s a totally private mall and insofar as the “city” designation implies some sort of “civic” identity, this is perhaps debatable. Whatever the case may be, take away the multi-functionality of a space and it becomes simply describable as its primary a function: a shopping mall, an exhibition hall, a food court, etc. It’s multiplicity that’s key for city rooms.

Does simply providing a place to sit count as a non-commercial function? If one can sit interrupted without doing anything or buying anything, I am inclined to say that it should. It may sound simple, but anyone who has spent enough time in a shopping mall without available places to sit knows that free seating is by no means to take for granted.

Perhaps “provision of a comfortable place where one can do nothing” should be another qualifier.

Supporting temporary exhibition-style events throughout the year. Like cities, city rooms are best when activated by more than permanent, year round eateries and shops. Their nature as large, usually flat, centralized collectors of activity naturally lend themselves to various temporary exhibits, performances, or activities.

After that rather tedious concept wrangling, it’s tempting to put forward an alternative, though dictionary-inappropriate definition:

A city room is a place that feels like a city room.

After all, the exercise above indicated that the words themselves are able to do much of the work in clarifying the definition. A city room is a room scaled up for the city that contains functional aspects associated with the city within it.

Alas, definitions must be more rigorous. So an alternative:

city room (noun): A large, multi-functional, pedestrian connected, publicly accessible space enclosed by an urban structure.

One final thought. Could one devise a scoring system of sorts based on the above qualifications? It’s an intriguing possibility, as it implies that there is a spectrum of city roomness, rather than what I had implied above which is that it’s an all or nothing proposition. It would also introduce ranking and competition. A city room Olympics!

8. Now we have a workable definition. But why should we care about city rooms?

To answer this, it is instructive to return to the New York POPS research. In the above referenced essay, Kayden went on to conclude that: “Although [POPS have] yielded an impressive quantity of public space, [they have] failed to produce a similarly impressive quality of public space.”

As far as I have observed, most of the city rooms in Singapore provide spaces that are accessible, comfortable, safe, well maintained, and well used. So far, I’m inclined to describe them as very high quality. It’s worth reiterating the point made in point #4 above: for me, city rooms are one of the pinnacles of the ordinary, everyday urban experience. They provide sheltered comfort in the form of architectural enclosure, ergonomic comfort in the form of places to sit, various functional amenities like markets, eateries, and cafes, and unexpected spectacles and events that lift the spirit make city life an appealing prospect. City rooms can be entered by any passersby on the sidewalk and inhabited for many hours, for free.

The reports say that humanity is becoming more and more urban, after all. We might as well make urban spaces the best they can be.

There is also some insight in the answer to a question that I asked a well known Singaporean public intellectual soon after I arrived here. (This person shall go unnamed as I did not ask for permission to quote them.)

The question was:

What do you think the United States can learn from Singapore?

The answer (after a long pause) was:

Probably something to do with doing more with less.

After all, that’s the basic notion behind the phrase “The Singapore Miracle”: a reference to the fact that this 30-mile (50km) wide country went from humble entrepot on the outskirts of a tiny tropical jungle island to highly developed nation in a matter of decades, all with practically no resources or hinterland of its own.

Plus, the ability to do more with less is a foundational idea behind sustainability, a topic of immense interest.

Which leaves me for now with a similar conclusion as in the first essay. Insofar as shapers of the built environment are interested in making active, functional, and accessible public space on development sites that have limited, urban footprints, the city room strategy is certainly not without precedent. When it comes to doing more with less in designing and planning public space, Singapore’s examples prove to be quite instructive.

I’m interested in examples of city rooms outside of Singapore. If you know of any, share in the comments section or send me a note at jamescarrico@substack.com. Especially interested in city rooms in the American context!

Text and photos © 2022 James Carrico

The similarity/distinction between “city room” and POPS is an interesting one. Highly enjoyed this more theoretical (?) yet more logical piece!

I like the use of a Venn diagram to illustrate your ideas. Keeping with this set-based perspective, is a city room a subset of a larger circle that some would call “the commons” (meaning both built and natural environments accessible to the public)?