~ 1,500 words, an eight-minute read

Huge thanks to friend-of-a-friend and fellow Fulbrighter Katie Schmidt for writing this guest piece for Plans in Perspective! As quick a personal note, I want to say that opening up this Substack to other contributors has been one of the most fulfilling things about writing on this platform, and that realization really hit me while I was working with Katie on this piece. It was seriously exciting to learn so much about a place I’ve never been. For PinP subscribers new and old, I think you’ll enjoy this one as much as I did. — James

How would you describe your relationship to your physical space? If you’ve ever moved, how would you describe the shift from feeling like a tourist to finding meaning in everyday places (your favorite coffee shop, your neighbors-who-just-had-a-baby’s apartment, that park you sweep every Saturday)?

In March 2022, I moved from my home in the United States to live in Lima, Peru for nine months on a research grant. As part of my own self-reflection on the impact of this experience on my life, I’ve been thinking about the difference between “space” and “place.” Specifically, “space” as a neutral, physical landscape and “place" as a realm defined more by human connection and meaning.

Geographer and poet Tim Cresswell describes these terms in his introductory textbook, Place: A Short Introduction, where he writes:

Place is… a way of seeing, knowing and understanding the world. When we look at the world as a world of places we see different things. We see attachments and connections between people and place. We see worlds of meaning and experience. (Tim Cresswell, Place: A Short Introduction, page 11).

Using this concept as a lens through which to view a particular built environment can help articulate experience and delineate meanings in our physical surroundings. With this in mind, I would like to discuss Parque Chino de Miraflores: a Chinese-garden style park that opened in early 2022 in Lima. By evaluating the park’s physical features, visitor experience, and political context in relation to the place vs. space dichotomy, I hope to arrive at a deeper understanding of what the park is and what it isn’t.

All photos taken by Katherine Schmidt.

Parque Chino de Miraflores

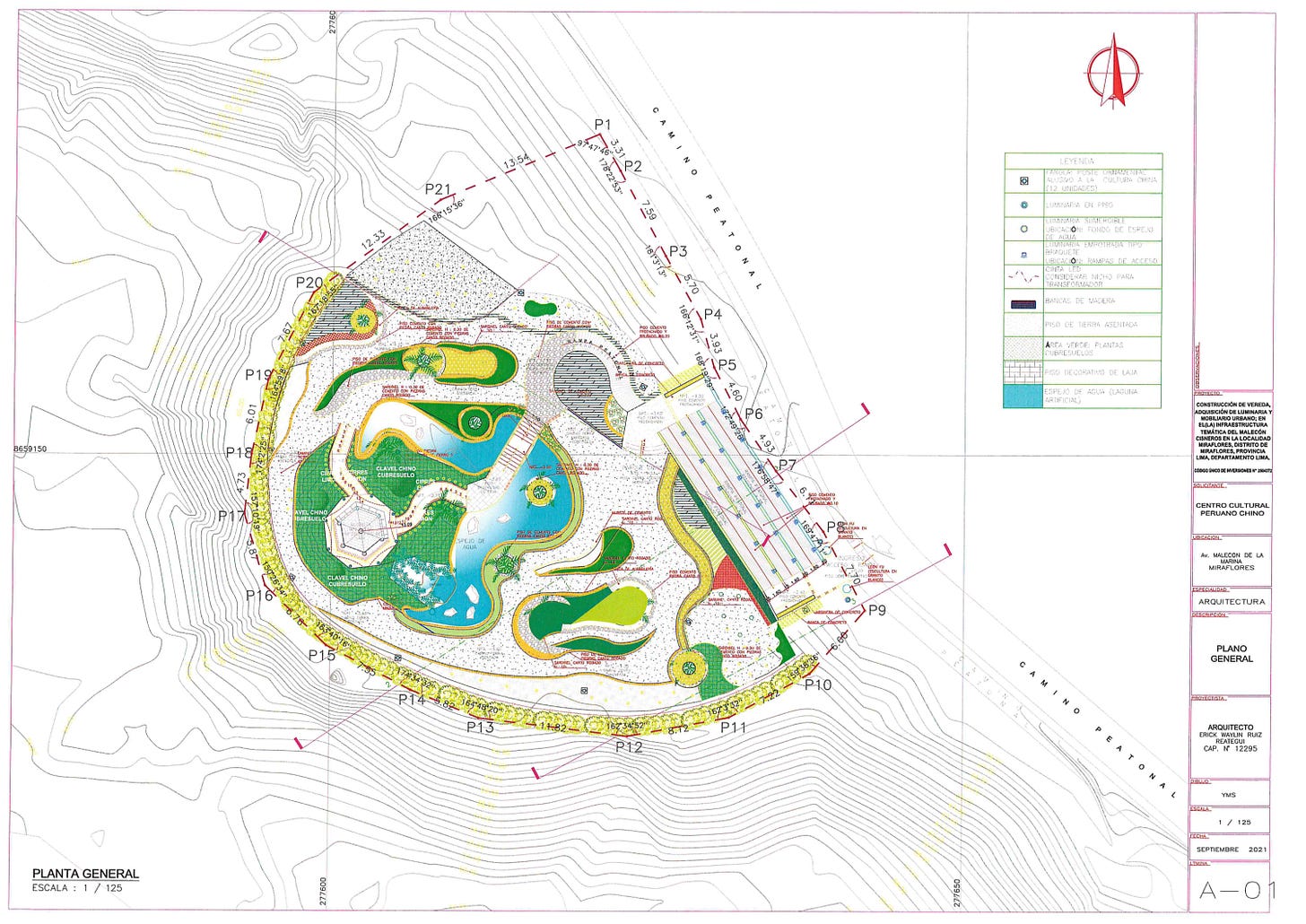

Parque Chino de Miraflores (“Chinese Park of Miraflores”) is a 1,500-square-meter (16,100 sq. ft) park located on the Miraflores Malecón — a five-kilometer (three mile) strip of parks, pedestrian walkways, and bike paths that sit on the dramatic cliffs that define urban Lima’s western edge and Pacific coastline. Walking the Malecón provides a picturesque view of surfers enjoying the waves of the Pacific Ocean, San Lorenzo Island, and the iconic Lighted Cross. Situated within this landscape, Parque Chino de Miraflores is visually defined by a Chinese pavilion that is visible from the walking paths and parks just north and south of it, as the park sits below the elevation of one of the Malecón’s main pedestrian thoroughfares. Below the park, the cliffside juts outward toward the ocean.

Lion, dragon, and Buddha sculptures are placed throughout the park, each accompanied by a plaque that describes their mythology and history. Perched on a tiny hill and accessed by a path that bridges a small pond, the pavilion is the clear centerpiece. It is also auditorily prominent with rooftop speakers that play a constant stream of Chinese instrumental music. (Note: this is not a unique case of the use of speakers in parks in Peru, Arequipa’s Plaza de Yanahuara does something similar). Although the sound of music in the pavilion is effective in setting the tone of “this is a Chinese park,” I find that it detracts from the kind of experiences I usually seek in other parks on the Malecón: to watch the waves, zone out, ponder the meaning of life, and so on.

Parque Chino de Miraflores is small and strictly planned. It's as if every paving stone and each blade of grass were accounted for in the design, allowing little room for serendipitous movement. As such, visitors naturally conform to a predictable and choreographed use pattern. Every time I visit I see steady waves of people in and out. The transitory nature of the park is partly because of its size, but it’s also because it lacks provision of areas for wandering or hanging out. Anything that is not a path is a fenced garden; the clearly demarcated edges of the paths sharply differentiate between zones for people and zones for plants and sculptures.

The pavilion, the bridge, and surrounding views provide Instagram-worthy photo ops; during a recent visit, I witnessed a quinceañera photoshoot. Although there are benches, I’ve never had the urge to hang out here. I can’t imagine anyone relaxing in it for very long. With the music, stark demarcation of the paths in the limited space, and continuous flow of visitors, most experiences in the park feel rushed.

I took a friend – an American historian – to the park and asked for her impression. She described it as “feeling like EPCOT,” a reference to one of the Disney concepts. It may be our American obsession with authenticity, but the juxtaposition between the ambiance of seriousness — conveyed by the plaques and planned experience of the park — and theme-park-like sculptures is jarring. The space feels less like it was built for the Chinese-Peruvian community (known as “Tusan”, from 土生) and more like a space for tourists to come, take photos, and leave. It feels more like a space than a place.

The Park as a Political Space

And in fact, the park wasn’t actually built for the Tusan community. According to the descriptive plaque at the bottom of the entrance ramp, Parque Chino de Miraflores was created to commemorate: 1) Peru’s bicentennial of independence; 2) 50 years of diplomatic relations between the People’s Republic of China and Peru; and 3) 127 years since the beginning of Chinese immigration to Peru. The Tusan association, Centro Cultural Peruano Chino, executed the project with support from the Chinese embassy and Peruvian Chinese community. The list of donors is included on the plaque and features the Association of Chinese Companies in Peru, Overseas China Affairs Office of the PRC State Council, the Chinese Embassy, Xiaomi Technologies Peru, and the University of Ricardo Palma’s Confucius Institute.

The park is a political space in the sense that it explicitly promotes a history and image tailored to interests of the countries, with awareness that the messaging will be highly-visible to both Peruvian and international audiences. The first plaque visitors encounter is titled “Los Chinos En El Peru.” The plaque walks visitors through a brief history of Chinese immigration to Peru, including a nod at the “unjust work conditions” that laborers (“coolies”) worked under, the creation of Lima’s Chinatown, and the rise of Chinese businesses. The last paragraph explains that the Chinese Peruvian community decided to construct the park in this specific location so visitors can look out over the Pacific Ocean to where China sits more than 17,000 kilometers (10,500 mi.) away.

(Note: for more historical background, see article “The Chinatown in Peru and the Changing Peruvian Chinese Community(ies)” by Isabelle Lausent-Herrera.)

Parque Chino de Miraflores joins other Chinese spaces and places in Lima. There are formal Chinese-state spaces such as the Embassy and Confucius Institute. There are formal locations of Chinese businesses, as well as formal Chinese-Peruvian spaces and places such as the various Tusan and Chinese cultural associations. On the other hand, informal community places include chifa restaurants (Chinese-Peruvian food, from 吃饭), Chinese-run bodegas, the historic Chinatown, the newer Chinatown popping up in San Borja, lawns where people practice Tai chi, and restaurants that serve as places where the Tusan and Chinese communities gather. State-approved and deliberately constructed to be a Chinese space, Parque Chino de Miraflores falls solidly in the “formal” category, though unlike many of the aforementioned examples it does serve a much wider public audience. People don’t stumble into Confucius Institutes, but people can spontaneously enter the park.

By examining the park’s features, the experience of walking through it, and its political origins through the lens of space vs. place, I argue that Parque Chino de Miraflores does not create a space for hanging out, nor does it allow for nuance in its telling of the history of Chinese immigration in Peru. It does not promote individual connection with Tusan culture or experience. To be clear, I’m not faulting the park for not being something that it is not. It does elevate the presence of Tusans and the state-to-state relationship between China and Peru. And by providing a manicured vantage point from which to view the crashing waves of the Pacific, it is an undeniably beautiful setting that’s perfect for pictures.

Of course, my understanding of Parque Chino de Miraflores is influenced by my research on Global China, as well as my academic background and identity as an American. Our connections with land and space are personal. They also change. Over the past few weeks, as I’ve worked on this post, I’ve gotten into the habit of herding my friends into the park while I ask them questions like “but what do you feel?” I will no longer be able to absentmindedly walk past it on my way to pick up lúcuma juice, or on a quick stroll down the Malecón. Amid the context of my deepening relationship with Peru — including finding meaning in various places — I now feel an increased sense of connection with the park. And now, Parque Chino de Miraflores and I are forever connected by this Substack post.

© 2022 Katherine Schmidt

Hi katherine, I just saw your text in Plans in Perspective, I find it super interesting, my name is Anjara I'm an architect here in Lima, I would like to know more from your perspective, If you like, contact me!