~1,200 words, a six-minute read

At some unidentifiable point in the later half of the previous century, the phrase “Architecture with a capital ‘A’” made its way into the field. I assume my own first exposure to the phrase, which was by hearing it spoken rather than reading it written, is indicative of how the idea spread itself around. Like most provocations with varying degrees of usefulness, I’m sure it emerged in academia somewhere.

A little searching — which surely doesn’t do just investigation to the phrase’s true origins — brings up two written instances (and one spoken instance) of the phrase. The first is a short article by Robert Bruegmann called “Architecture Without the Capital ‘A.’” written in 1986. The second is a short documentary called “Architecture with capital letter ‘A’.” It features the Japanese Architect Arata Isozaki saying:

I have learned from Palladio what is architecture. Architecture with a capital “A” — this is kind of almost, for me and many architects, impossible to explain directly.

Bruegmann tries anyway, writing:

. . . unlike the magnificent cold storage warehouse or the interesting 1950s subdivision with the unusual trimmed hedges that we did not stop to see, the Frank Lloyd Wright garage was the product of a certifiably “important” architect. Such is the power of the notion of Architecture with a capital “A.”

Piecing this all together, the idea could be explained with a simple diagram:

Just a little joking, this. And anyway, “Architecture with a capital “A”” is probably more recognized as a spoken phrase rather than as actual guidance for capitalization in written English. But it sets the mood for the next section of this post.

As I wrote last week, I submitted “city room” to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). I put up a copy of the full submission on a standalone Substack page here, if you want to see it. Two quick points on that. First off, I’ve never been called a nerd this many times since high school. (Except this time, it’s coming from Instagram, which didn’t exist back then.) Second, and I’m not sure if this bothers anyone or not, but know that the draft definition listed in my submission (“a bustling, covered public space that facilitates various events and activities, usually located in a large open area at the ground floor of an urban building”) will almost certainly not be the official definition if it’s ultimately accepted. It’s really not up to me alone, since apparently there’s a pretty long process this would go through at OED.

(And if this was bothering you…that also makes you a NERD!! Hah hah hah.)

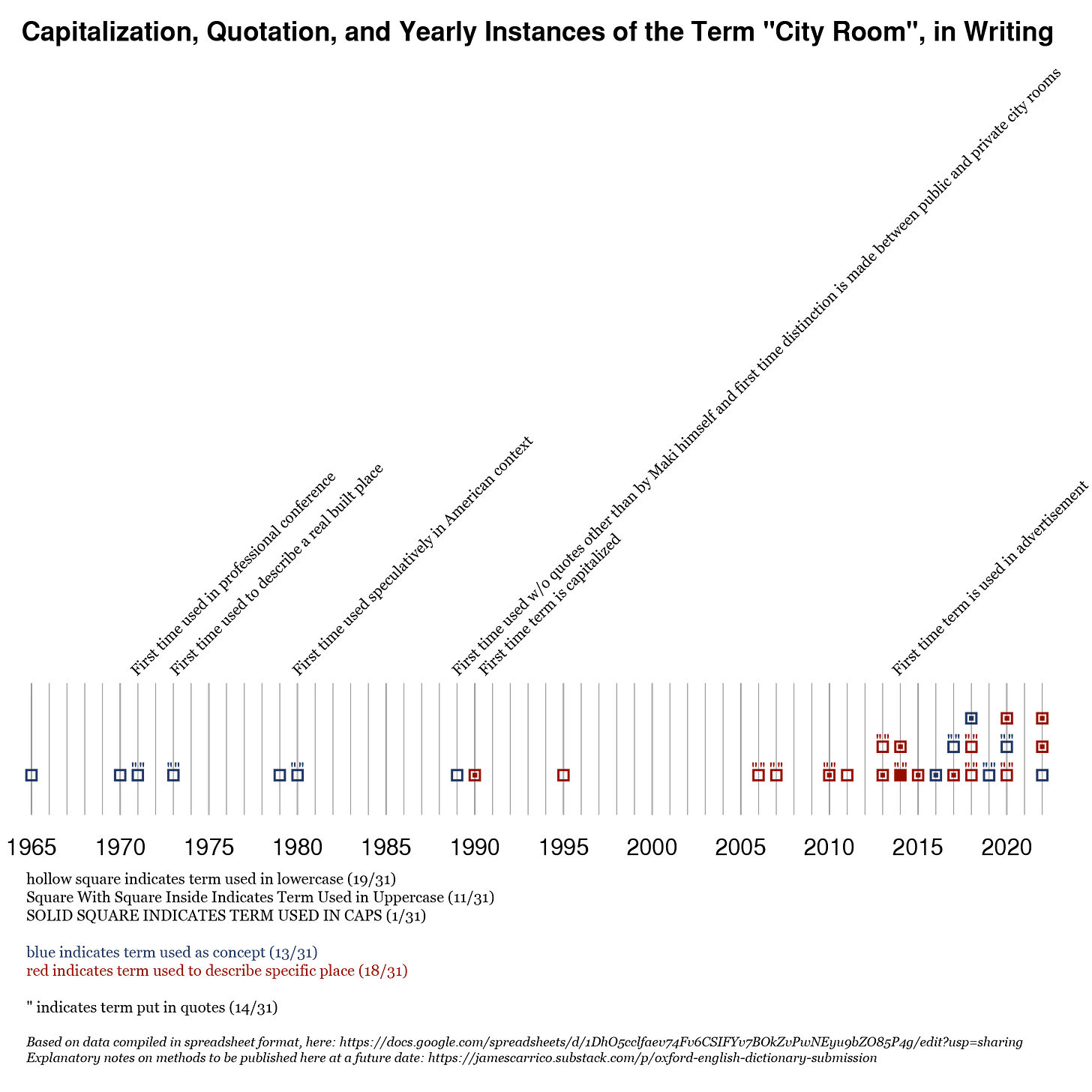

Anyway, the exercise was a good one since it forced me to comb the Earth looking for instances of the term in written form. In total, I found it in about 30 different places between 1965 to 2022. (Notes on my methods are forthcoming and will be listed on Substack but somewhere else…I’ll spare you for now.) Indexing those occurrences of the term leads to some interesting results, especially when things are charted graphically. Take a look:

A lot to think about with this information, and depending on your opinions about urban planning and real estate and the intersection of the two, the increasing frequency of the term post ‘08 is either frightening or exciting. But that’s a nightmare to unpack another day.

For now, I want to focus on the capitalization issue. Two things. First, the term “city room” was originally conceived as a common noun, and it was not written in capitalized form (“City Room”) until 25 years after its first occurrence in print. Second, insofar as the concept is now understood as a type of urban space, not one particular place, capitalizing the term makes about as much sense as capitalizing the term “shopping mall” or “bedroom” or any one of the 700 compound nouns that end in “-room”. Yet there it is capitalized in 11 out of 31 instances.

I suppose we can forgive William Lim, who was the first to capitalize the term in 1990 when he was describing the atrium space at People’s Park Complex (PPC). First come, first serve with making proper nouns from common nouns, I guess. But even then, to capitalize it this time would imply that the PPC city room was the One City Room to Rule Them All.

And city rooms were never intended to be made only once. And sure enough, capitalized city rooms did not stop at PPC. In the past decade, at least four buildings that have bustling, covered public spaces that facilitate activities and events at ground level are vying for the capitalized version of the term. Admittedly I’m not a linguist I don’t think a proper noun can refer to four places at once.

So, it’s a real mess we’re in! It’s reminiscent of the “Architecture with a capital “A”” thing. Perhaps the tropical heat is loosening my bearings, but this time I’m keen to steer the ship away from architecture English and back toward Standard English. “What ship…and who’s on it?” you may ask. I don’t know. (Nobody does.)

But, back to the issue at hand. There is a dark side lurking behind the proliferation of a thing identified by a proper noun. That is to say it seems they are by definition rightfully locked-in to their ultra specific meaning and connotation. Stuck. Des Moines can’t be anything else besides Des Moines. On the other hand, “the monks” could refer to an ever evolving cast of characters. For city room, that would mean in literal terms that William Lim’s use of the capitalized 1990 term was referring to the only city room that could ever be identified as such. It boggles the mind to imagine how a space claimed as distinct can have multiple incarnations. What would that look like even…a People’s-Park-Complex-replica every time? The mere speculation of a quickly metabolizing yet proper-noun-identified space type quickly tilts us all into a state of tyranny. A City Room in every pot. I shudder to think about it.

Or the alternative is it becomes some sort of branded thing. But that also sponsors indigestion.

But and yet here we are, with at least 11 capitalized instances (plus the crazy advertisement where every single letter is caps...let’s not talk about that). I can think of two ways out. The first is that OED accepts the submission and forever enshrines the term as a generic, lower case, compound noun. This is the way it was originally intended by The Metabolists of Japan, after all. The second would be if these quickly emerging city room spaces qualify themselves a little bit, i.e. “Acme City Room.” There’s always the good ol’, corporate sponsorship route, but perhaps in this brave new world of user-experience consultants, more creative identifiers will come about.

If they do, I’ve got a nice spreadsheet on which to make note of them.

Or, let’s just use city room in lowercase and let the term’s meaning evolve organically. With the market, as they say. That way not me, not another academic, not a real estate developer, and certainly not some government planning agency can take it as theirs.

© 2022 James Carrico