Back to the Future with Urban Air Mobility

From streets and sidewalks to highways in the sky.

~1,800 words, a nine-minute read

THE PLAN:

THE PERSPECTIVE:

MY TAKE:

It's been eleven years since Peter Thiel authored the viral contrarian phrase: "We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters." Today, I want to explore a natural follow-on: “What if we finally (!) get flying cars?”

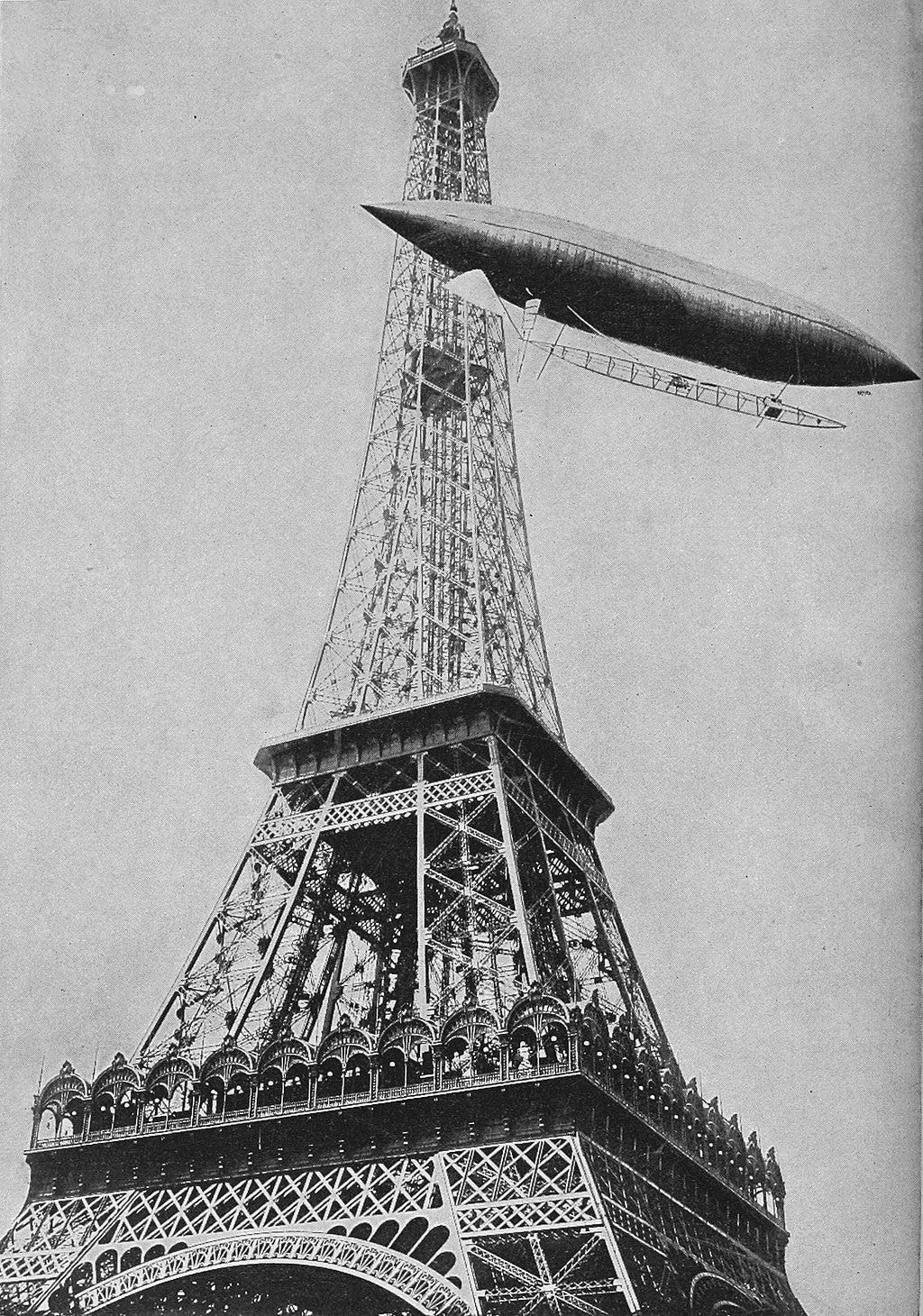

Flying above crowds has long been in the human imagination. Balloons got people into the air as early as the 1780s, but they weren’t practical for transportation…being at the mercy of the winds. It wasn’t until the turn of the 20th century that steerable balloons called dirigibles became controllable enough (sort of) to use within the confines of a city. In the early 1900s, lucky Parisians saw an early version of urban air mobility in the form of Brazilian inventor Alberto Santos-Dumont out for a flight in one of his personal dirigibles. Rich though not idle (he was heir to a coffee fortune back home), Santos-Dumont was an inventor of both floating and winged aircraft and literally crashed into French high society in his errant creations.1

On the big screen, aerial vehicles have been routine background features in sci-fi films since the low flying planes in Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis. More recent reincarnations are Bladerunner Spinners and Airpeeders in Star Wars. Even Norman Bel Geddes’ expressway-laden vision of 1960 — showcased at the 1939 World’s Fair Futurama and captured in a film documentary To New Horizons — included circular airports (for dirigibles!) and buildings with “landing decks for helicopters and autogyros.”2

While Santos-Dumont’s Parisian flights remained a novelty, in the late 1930’s Igor Sikorsky, father of the modern helicopter, pursued and achieved — for some —his dream of “flying from anywhere to anywhere.”3 The helicopter enabled scheduled air taxi services from compact landing zones, including tops of buildings. In the 1950’s, a helo-based version of urban air travel took flight in several US cities. Perhaps most notably and most highly visible, New York Airways operated helicopter air taxis between the three major New York City airports and by 1965 had extended the service to Manhattan, ferrying passengers from the top of the Pan Am building to LaGuardia in less than 10 minutes.4 Urban air mobility (UAM) had arrived…or had it?

Visions and visionaries gloss over pesky details that complicate actual implementation. Geddes’ expressways are anything but at rush hour. Santos-Dumont’s balloons were not quite steerable enough, even for recreational use. Helicopters, while tremendously useful for some applications like medical transportation and servicing oil rigs at sea, are not in every driveway or on every rooftop as Sikorsky envisioned, having been undone by noise, operating costs, and safety concerns. New York Airways folded in the 1970s after several tragic accidents and poor balance sheets.5

Today, however, a new class of battery-powered small aircraft have the promise — at least on paper — to fix those concerns. Called electric vertical takeoff and landing vehicles (eVTOLs), they use multiple electric motors and rotors for quiet, redundant, and green propulsion.

Considerable venture capital is funding eVTOL development projects around the globe. Dozens of start-ups — not to mention traditional airplane manufacturers like Airbus and Embraer — are designing and flight testing a variety of prototypes. Some have both wings and rotors to combine the utility of vertical takeoff and landing with the energy efficiency of wing-borne cruise flight.6 Some have fixed rotors only — like a helicopter, but with multiple blades and motors. Some have pivoting wings and/or rotors to transition from vertical to horizontal flight. Others fold and stow the takeoff/landing rotors and use separate pusher rotors for cruise flight. A common factor in the designs, as their name implies, is the ability to take off and land in tight spots and the use of batteries for primary power (though designers are considering hybrid configurations using hydrogen as a fuel — Santos-Dumont would approve!).7

In the near term, most eVTOLs will have a pilot, but fully autonomous or remote pilot operation is a long-term goal to increase payload capacity and range. As these new vehicles complete flight testing and enter initial service over the next few years, the potential of these new designs to safely and routinely operate in urban environments will be determined.

For this paper, let’s restrict ourselves to passenger-carrying vehicles (small whiny delivery drones take us down entirely different paths...perhaps a future PinP article). Let’s also assume — and this is neither easy nor assured — these new passenger air vehicles are found to be safe-, quiet-, and efficient-enough for urban use in significant numbers…maybe hundreds or thousands operating within a city. Then what? Does the vision hold up? What will these flying cars be doing, who will use them, and what are the implications for the built environment?

Let’s consider some proposals either announced or on the drawing board:

Santos-Dumont’s leisurely aerial strolls? Check. In Singapore, eVTOL developer Volocopter is proposing tourist flights over Marina Bay and Sentosa.8

Sikorsky’s ‘live anywhere, work anywhere’ vision? Check. eVTOL developer Joby is working to introduce regional air ridesharing services to South Korea using eVTOLs capable of ferrying 4 passengers 150 miles at speeds up to 200 mph.9

Medical emergencies? Check. eVTOLs could replace or augment this niche currently filled by (noisy and expensive) conventional helicopters.10

Congested aerial highways? Check. What a minute!…congestion is what is trying to be avoided. More on that later.

As to who will use these vehicles, one airline executive put it succinctly, “[urban air mobility] will provide an ideal solution for those wishing to move faster through the city” (emphasis added.)11 Industry press releases appeal to broad frustration with urban congestion. Yet, even using the industry’s rosiest growth estimates, it is hard to see aerial vehicles offloading an appreciable fraction of surface traffic.12 Urban aerial travel may instead become, like Disneyland, available to the masses only as an infrequent treat. Those wanting to “move faster through the city” will likely pay a premium for the service, meaning UAM is not a mass transit solution…at least not in the near- or even mid-future.

Still, some fear “sky congestion” if increasing eVTOL numbers simply transfer surface gridlock to some form of aerial gridlock. (Think long lines of airspeeders on planet Coruscant in Star Wars — though probably without the leaping Jedi). Others fear intrusion of privacy: snoopers from above. And despite assurances from the eVTOL manufacturers, some still fear noise: takeoff and landing might still be annoyingly loud even with new propeller technology.13

Aerial vehicles that are safe, quiet, and efficient are one piece of the aerial mobility puzzle. Integration of routine aerial operations into a dense urban environment that enhances livability by addressing the congestion, privacy, and noise issues while providing equitable access is another. Large numbers of eVTOLs operating in tight urban spaces need organized traffic flows for efficiency and safety. Although eVTOLs can land and take off vertically, they cannot stop as quickly as a car, and hovering draws down the batteries. In short, stop signs and stop lights can’t be used to deal with crossing traffic or traffic slowdowns. For maximum efficiency, an eVTOL should be able to fly to its destination without stops or detours. Cities, agencies, and industry groups are working on aerial traffic concepts that address some of these concerns with “highway in the sky” concepts.14

Highways in the sky are defined aerial routes or “UAM corridors,” that confine eVTOL traffic to pre-approved paths and altitudes with defined boundaries, akin to the predefined routes in upper airspace used by commercial airliners, but scaled down for dense, low level flying among the skyscrapers.15 In practical terms, think of them like an invisible network of hamster tubes and elevator shafts...though unlike a hamster tube, the routes are much wider than the vehicle, potentially fitting multiple traffic streams into a single “tube”, and the “walls” of the elevator shafts may not be perfectly vertical (though still much steeper than the typical 3 degrees (from horizontal) landing glidepath of a conventional airplane).

UAM corridors have horizontal and vertical elements that define a 2D route over the ground and a 1D vertical component that defines the altitude of the route above the ground. Vertical-ish “shafts” provide access to landing points (“vertiports” in UAM lingo). In practice, the corridor will likely be defined by its centerline with the eVTOL required to stay within a specified distance and altitude of that line. The corridors might someday evolve to "4D" routes when a time element is added, constraining the eVTOLs to be "at a certain point at a certain time" for traffic flow and separation purposes.

For the flyer, aerial corridors provide a framework for keeping away from fixed obstacles like buildings and towers, separation from crossing or opposing traffic, and orderly flows into busy landing sites. The corridors also serve to keep eVTOLs away from delivery drones and large airliners. Freedom to operate within defined boundaries.

For the city dweller, aerial corridors keep the noise and sight of aerial traffic away from sensitive areas like neighborhoods and parks. The corridors are a manifestation of municipal will as to where and how this new transportation mode fits into the urban environment. Freedom from unwanted aerial intrusion.

In this light, UAM corridors can be thought of as policy instruments that reflect the negotiated needs of multiple stakeholders...akin to corridors and elevators in a building. Flyers use them for safety and efficiency. City dwellers use them to establish community-acceptable compromises between aerial network access versus privacy and quiet. Just like an elevator shaft where everyone wants to be close, but not too close, to the elevator lobby, city dwellers will want convenient access to vertiports, but won’t want to be too close to the noise and visual distractions of a busy stream of arriving and departing eVTOLs.

To the degree that aerial corridors express the will of municipal residents and municipal governments (okay to fly 'here', but not 'there'), the aerial corridor concept is likely to be a durable yet contested feature of cities long into the future. Even after advanced on-board technologies enable eVTOLs to operate autonomously and avoid other aircraft without predefined routes, UAM corridors will remain viable expressions of a community’s transit vs. livability values.

© 2022 Matthew Carrico

Despite Santos-Dumonts efforts, balloon and dirigible travel within cities remained a novelty, primarily due to steering issues and challenges with using gaseous hydrogen (large dirigibles were used for long distance travel in the 1920s and 1930s until the Hindenburg disaster). After his lighter-than-air prototypes, Santos-Dumont turned to heavier-than-air vehicles and publicly flew his 14-bis biplane in Paris in 1906. Santos-Demont is regarded as an aviation pioneer in his native Brazil, right up there with the Wright brothers. No doubt he was more flamboyant about it.., floating around Paris in small balloons and dirigibles of his own making. You can dive deeper into his life with Paul Hoffman’s biography, Wings of Madness: Alberto Santos-Dumont and the Invention of Flight, Hachette Books, 2003.

Futurama was a large (~1 acre/0.4 hectare) idealized model of life twenty years into the future–the 1960s. The centerpieces of the exhibit were 14 lane automated highways interconnecting extensive suburbs and sleek city towers. Sponsored by General Motors Corporation, aerial vehicles were (naturally) only briefly mentioned. You can see a narrated video tour of Futurama titled, To New Horizons, at this link:

Sikorsky described his prescient vision for everyday use of helicopters in a magazine article, “The Coming Air Age.”, The Atlantic, September, 1942. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1942/09/the-coming-air-age/306248/

I’m not saying helicopters aren’t safe–they are–but high profile accidents are a factor in public perception. A tragic accident occurred in 1977 at the top of the Pan Am Building (now MetLife). While on-boarding passengers, a New York Airways helicopter experienced a mechanical failure, killing four boarding passengers and one pedestrian on the ground from falling debris. You can read the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) report on the NYA accident here: https://libraryonline.erau.edu/online-full-text/ntsb/aircraft-accident-reports/AAR77-09.pdf

“Wing borne flight” refers to the lift generated by the wings to keep an airplane in the air Compared to power-hungry rotors used for vertical takeoff, generating lift using a fixed wing is much more energy efficient for cruise flight.

eVTOL development is a hot item right now. You can keep up with this fast paced industry through industry newsletters. This one, FutureFlight, offers a free weekly newsletter: https://www.futureflight.aero/

https://www.ainonline.com/aviation-news/air-transport/2022-02-14/urban-air-mobility-could-deliver-s4-billion-boost-singapore

https://ir.jobyaviation.com/news-events/press-releases/detail/26/skt-and-joby-join-forces-to-bring-air-taxi-service-to-south

Cowen, Gerrard. “How eVTOL aircraft might find their way into EMS.” eVTOL, December 2, 2019 https://evtol.com/features/evtol-aircraft-prospects-ems/

“Flying Over Traffic Jams,” Aerospace America, AIAA, June 2022

To see why this is true, consider Los Angeles, CA, where major freeway each carry tens of thousands of cars every hour, there are about 100,000 rideshare drivers, and about 91,000 people ride the light rail system daily. Hundreds, or even a few thousand, 4-pax eVTOLs will not make a dent in these numbers. Sources: 1) https://dot.ca.gov/programs/traffic-operations/census ; 2) “Los Angeles Rethinks Taxis as Uber and Lyft Dominate the Streets,” Susan Carpenter, New York Times, January 12, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/12/business/los-angeles-taxis-uber-lyft.html; 3) https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/2021-Q4-Ridership-APTA.pdf

The eVTOL industry regards managing the ‘noise problem’ as critical to its success. Numerous studies and trials are underway to assess the vehicle noise characteristics and establish community-acceptable noise levels. A good place to dig deeper is this report from NASA (USA): Urban Air Mobility Noise: Current Practice, Gaps, and Recommendations, NASA, October 2020, NASA/TP–2020-5007433 https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20205007433/downloads/NASA-TP-2020-5007433.pdf

Regulators, agencies, municipalities, industry groups, and manufacturers around the globe are investigating operational concepts and regulations for these new vehicles and uses. Not surprisingly, much of the initial work has been done by the existing civil aviation authorities and aviation research groups such as the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the UK Civil Aviation Authority, and US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). More recently, municipalities and tourism agencies are jumping in with their considerations and priorities.

One major consideration for where to place the UAM corridors is the availability of suitable emergency landing places within gliding distance of a disabled eVTOL. This highly critical consideration is made even more challenging by the congested areas and low altitudes where eVTOLs fly. For the technically minded, here is a survey of other considerations and design alternatives for urban airspace: “Designing airspace for urban air mobility: A review of concepts and approaches,” Aleksander Bauranov, Jasenka Rakas, Progress in Aerospace Sciences, Volume 125, August 2021. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0376042121000312 .

© 2022 Matthew Carrico

I really enjoyed reading about the history and future of these aircrafts! eVTOLs seem promising but I can totally see how the flight paths will be the next frontier of NIMBY, especially considering that there will have to be set access points from the ground to enter/exit these machines not unlike a traditional bus or train station. Almost feel like instead of solving a problem we are just recreating it on another elevation… but I hope I am proven wrong!!