Dropped Edge, Lifted Spirit

Views, which command great cultural and financial value, are a lot better when the damn guardrail isn’t in the way.

~900 words, a five-minute read.

Here is a design move that doesn’t get enough mainstream appreciation:

I will explain.

Architectural spaces like rooftop terraces, boardwalks, and residential decks often have to content with clunky guardrails. Now clearly, these are often necessary for safety reasons. I am not advocating for their cancellation. I am not a cat.1

But still. Can something be done to reduce their girth, their imposition, their soul-crushing heft? Their dastardly assault on the occipital lobes?

A good architect should know. And you too, after reading this, will recognize when you’re on a well designed deck. Point it out in company and impress.

Faced with a guardrail requirement for decks or platforms, a good tactical design response involves lowering the last four or five feet of floor by a few steps.

From the perspective of the now lifted upper section, there is a sense of elevation. The guardrail may not disappear entirely, but it will look far shorter than the mind expects. A less-interrupted view emerges, especially the part below the horizon. And that’s one of the best parts of a view.

Unfortunately, there are often practical reasons this maneuver cannot be done. It requires physical depth, structural finesse, and there are building code considerations too: adding steps often means adding corresponding handrails. Still, a good architect (like WOHA Architects, who did the building pictured above) will skillfully integrate all of this into a larger ensemble of planters and canopy-supporting walls.

Architects aren’t the only ones concerned with views. A recurring topic in urban planning theory and landscape scholarship is about the notion that humans have a primordial desire to seek out vantages over the surrounding territory. There is something deeply important about the ability to comprehend our daily ground-level patterns from a higher viewpoint. A bird’s-eye over surface trudgery. I’ll leave it to PhD’s to explain why this is, exactly.

They certainly are trying, after all. Because while appreciation of the idea may go back centuries or more, it’s an active subject of study now too. A 2020-published article called “Urban views and their impacts on citizens” looks at vantage points around the city of Sanandaj in Iran. The somewhat cryptic punchline, which seems to support an evidence-based argument in favor of view quality, is:

The results showed that in general, urban views do not create positive or negative emotional responses among citizens but rather the quality of urban views make desirable or undesirable emotional responses.

It’s a little tricky to unpack that, but I’m left with a sense of appreciation for the fact that the authors took the effort to analyze “twelve types of urban views”, cited 40 other works, and still concluded that “further and broader research” is in order.

It’s reminiscent of geographer Jay Appleton’s influential proposition that humans are wired to feel more comfortable in spaces perceived to have qualities of “prospect” (places one can see from) and “refuge” (places one cannot be seen in).

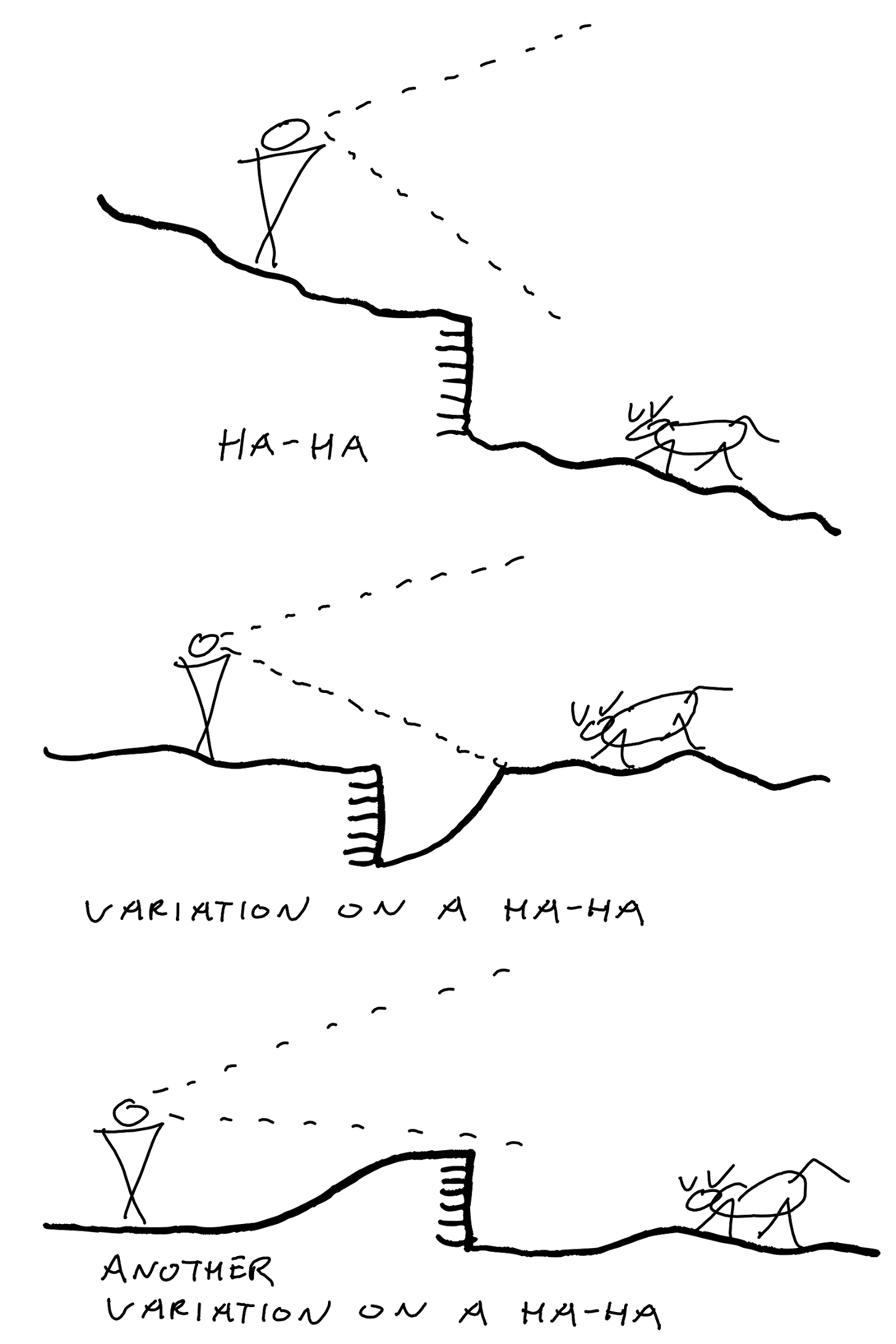

Speaking of geography, there is something of a landscape equivalent to the architectural dropped edge. It’s called a ha-ha wall. I am not making this up. The ha-ha wall refers to a wall that is embedded in a slope of ground. The intent is to obscure the disruptive sight of the barrier — itself often necessary for practical reasons like livestock containment — which would otherwise interrupt the visual continuity of a natural, flowing landscape. Those picturesque pastoral scenes of undulating green grass fields we know and love.

Rumored to be named like so because Louis XIV’s son once laughed at a wall in the ground, the ha-ha wall has an above-average Wikipedia page. It can be configured in different ways depending on the topography or desired landscape design.

Cultural studies aside, there is of course money to be made on views. This is surely true in both architecture and landscape architecture. After all, property developers pay top-dollar for expensive glass towers that clad transparent every last possible square inch of vertical surface. Anecdotally speaking too, on a recent tour of a hotel, I was informed I could upgrade to stay in a room with floor-to-ceiling glass. Priced accordingly in relation to those inferior rooms with “normal” windows, surely.

As far as I know, no one has done a high-quality analysis on the correlation between cost and return on uninterrupted views vis-a-vis railing configuration. Perhaps that’s a subject for the further-and-broader-research category.

Finally, the dropped edge technique isn’t just for public housing rooftops in tropical nations, or luxury condos in some shiny star-architect designed catastrophe, or as fodder for humanities scholars. If there’s enough room in the yard, it’s a potential tactic for many a cedar deck, that beloved staple of the American single-family abode.

Since urban dwellers enjoy the prospect of the city, so do the lords and lordesses of the home seek visual dominion over their land, right beyond the edge of the planks. That’s where architecture stops and landscape, that thing most of us would rather observe if we’re being honest thank you, begins.

Know an example of a good dropped edge design? Let us know in the comments.

© 2022 James Carrico

Below the Line:

Architecture in the news: “The Hotel Is 642 Feet Tall. Its ‘Architect’ Says He Never Saw the Plans.” (New York Times)

International Real Estate in the news: “Inside Forest City, a $100 billion 'dream paradise' turned ghost town” (Insider)

Infrastructure in the news: “Inflation Taking Bite Out of New Infrastructure Projects” (Associated Press)

Plus:

In last week’s article, the most clicked-on link was the Wikipedia page for Pier Mondrian’s painting: Victory Boogie Woogie

If you know, you know.