This is somewhat half cooked, but I really wanted to get it out before April 19th, where here around Boston, the 250th anniversary of the beginning of the Revolutionary War is being commemorated. I’ve been writing parts of this in my head for several weeks, but never really managed to carve enough time to flush it out properly. There’s a lot of nuance to the historical events that unfolded during and after Revere’s ride, not to mention the various architectural histories of churches and meeting houses in New England that I hoped to better understand, but that will have to be for another day. A deadline is a deadline, the moon is rising again as it was 250 years ago, and I’m clicking send on what I got. Enjoy! And Happy Semiquincentennial!

By the seasoned age of 44, the painter of the captivating scene shown above was just getting around to writing one of his only published written works. In his essay “Revolt Against the City”, Grant Wood asserted that American painting was increasingly being appreciated on its own terms, freed from the influence of “foreign and imitative work…away from Paris and the American pseudo-Parisians.” This led to Wood’s thoughtful position on the form of his own patriotism:

If it is patriotic, it is so because a feeling for one’s own milieu and for the validity of one’s own life and its surroundings is patriotic. Certainly I prefer to think of it, not in terms of sentiment at all, but rather as a common-sense utilization for art of native materials–an honest reliance by the artist upon subject matter which he can best interpret because he knows it best.1

I begin with this because it is April 2025, and here around Boston, Massachusetts, Patriotism is in season. This Saturday, big bashes are planned to celebrate the semiquincentennial of the Battles of Lexington and Concord. And I’m participating, by attending the reenactments of the Battle of Lexington followed by a skydiving performance by the U.S. Army Golden Knights, followed hopefully by pancakes and perhaps a viewing of a model of the historic Battle Green Meeting House made by Lexington resident Ben Soule. But first, I’m writing this short essay about a painting I like.

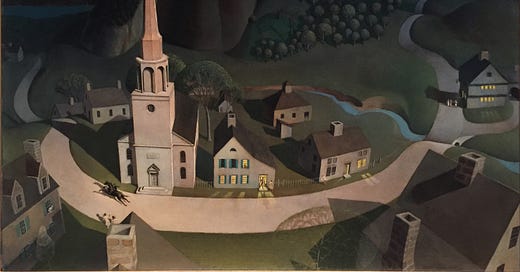

For Wood, love of country was an automatic and complementary extension of his love of locale, which in his case was the rolling country farmlands of eastern Iowa. And no painting of his better synthesizes the two than Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, the dreamy portrayal of the fabled scene on the eve of the Revolutionary War. In it, Wood depicts Revere on his horse galloping through a moonlit Lexington, with its great towering steeple and assortment of humble colonial structures. But peer a little further into the darkness, and the surroundings cease to resemble the quaint New England village. The larger landscape backdrop for Wood’s ride is none other than the cliffs of Stone City, Iowa, easily recognizable from another of Wood’s well-known paintings. Revere was not just riding for all of America. In Midnight Ride, he literally rides through it.

Wood plays other games with buildings in this painting. His depiction of Lexington isn’t really accurate, which of course is fine — Wood is an artist, not an architect, after all. But that does raise the question about what these buildings actually are, and a couple stand out. One of the houses in the back looks suspiciously reminiscent of the Old Belfry structure in Lexington; this is the bell that rang the alarm prior to the Battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775. And I am certain that the house off to the right is directly based on Paul Revere’s actual house: pitched roof, boarded square in the gable, slightly cantilevered volumes differentiating first floor, second floor, and attic. The scene of the evening is completed with this “beginning”: Revere presumably galloping right out of his house. With the house on the right side of the image, one can read the overall composition of the painting as a kind of reverse timeline of Revere’s ride.

There’s also a very interesting detail, which is that the house is painted along with its little sign on the corner of the building. Anyone who’s visited the house in Boston knows the sign says “Paul Revere’s House”, a modern-era wayfinding artifact for the many visiting tourists. But Grant Wood painted it right into Midnight Ride, toying not only with space but also with time. To this point, it’s worth adding that Wood was explicitly inspired by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous poem "Paul Revere's Ride" which was written in 1860, 85 years after the original event took place. Further, the poem itself is known for somewhat fictionalizing some aspects of the events. Still, Longfellow’s portrayal has unquestionably become the driving narrative behind the Paul Revere story as it is understood in our national culture. (Another tangent for another time, but perhaps the victory of writing as a dominant cultural medium over painting?) (For a fascinating bit of comparison, read both Longfellow’s poem AND Revere’s own account of the events, here.)

And then there’s the primary civic building — called a church by some or a meeting house by others — with its soaring steeple that anchors the image. Again, this building exemplifies how Wood blended different references from built reality into something fictional, the result bordering on the surreal.

The immediate assumption would be the building is the First Parish Church in Lexington, which does indeed have an impressive steeple. But a closer look shows several inconsistencies: the lack of classical portico being the most obvious, with a whole host of other massing, parti, and other architectural differences in the tower and facade. The triangular pediment over the door in the painting implies a more secular nature to the building, but it could easily be understood as a church. This may have been an intentional and logical blend of the dual-duty meeting house functions and church going functions that these kinds of New England buildings often performed. There’s a time thing going on here too: Lexington’s current First Parish Meeting house wasn’t built until 1948, 73 years after Revere’s ride.

However, the building does more clearly resemble two other structures in nearby Boston, both of which played a role in the Revolutionary War and therefore easily become fair game for Wood’s painting. The steeple clearly bears resemblance to the one at the Old South Meeting House, where colonists often gathered to organize such things as the Boston Tea Party. The other building is the Old North Church, more famously known as the location where the two “if-by-sea” lanterns were lit. Wood’s building borrows its parti of the single bay of aisle windows, and the rectangular plaque.

Around Lexington and Concord, questions of historical accuracy have been springing up. Which town was the site of the "shot heard round the world"? (For the record, the answer is CLEARLY Lexington.) Who actually hung the two lanterns? These are fun questions to debate, but I think Grant Wood would say we shouldn’t sweat it too much. We are the stories we tell ourselves, not the factual idiosyncrasies we squabble over. And as this anniversary approaches, Wood’s patriotism by means of localism, manifest in the form of Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, will give me a source of reflection throughout the weekend’s festivities.

Wood, Grant. 1935. Revolt against the City. Iowa City, Ia.: Clio press.