If you’re an architect, and someone invites you inside an otherwise privately accessible building, you over-earnestly accept. During the visit, you continually shower your host with gratitude. Too much gratitude, probably, because they start to think something is wrong with you. But there’s nothing wrong with being curious about the indoors. They may just be the only places on earth not voyeured to death by satellites and street view cameras. So they’re unique and personal, uncommodified in a way that discoverable public places aren’t. A scarce yet invaluable resource for the lifelong education of an architect.

This was a key premise of a successful Fulbright research proposal I submitted in the fall of 2019. “Give me $30k to go live in Hong Kong for 10-months,” I wrote. “I’ll study how the indomitable human spirit makes habitable interior environments against the odds in the most crowded metropolis on earth. We will learn how to do more with less.”

Of course, I wrote it more carefully than that. Reluctantly, but at the suggestion of some of my mentors, a brief reference was made to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. But the gist of it was to spend the better part of a year measuring, photographing, drawing, analyzing, reading about, and meeting people inside some decaying concrete mixed-use buildings built in Hong Kong back in the early 60’s. Turns out the Fulbright review committees (there are always two, one in the U.S., and one in the host country) liked it enough to award me the sole research position available for Hong Kong for the 2020 academic year. I’m not writing this to boast, but to tee up a key reflection. That is: I am certain the success in the proposal wasn’t so much because it paid lip service to the deep state (UN SDG), but because of the specificity by which it defined the subject matter. And that’s where Mei Wah Building (美華大廈) comes in. Literally: Beautiful (美 mei5) Magnificent (華 waa4) Building (大廈 daai6haa6).

Side note: many people have asked for a copy of this proposal (called a “statement of grant purpose”): inquisitive classmates, academically inclined colleagues, moms with college-age kids...I’ll write here what I told them: I’m not sharing it, I’m never sharing it. Figure out your own research proposal. Everyone’s better off that way, especially you. That said, if you’re an architecture student and want to go after something like this, hit me up. More architects should do things like this, and I can be of support in other (better) constructive ways.

Beautiful Magnificent Building was identified in my Fulbright proposal as an exemplar of the issues I wanted to investigate. Luckily, my venerable academic advisor in Hong Kong had (somehow) full access to the interior of the building. Jackpot.

But fate would not have it so. 2020 proved to be a terrible year to receive the promise of a life-changing engagement in a foreign country. Partly because of Covid, but in my case, moreso because of a tiny provision buried in Executive Order 13936: The President's Executive Order on Hong Kong Normalization:

Sec. 3 (i) take steps to terminate the Fulbright exchange program with regard to China and Hong Kong with respect to future exchanges for participants traveling both from and to China or Hong Kong;

I could, but I’m not going to, write for hours about how deeply I got involved in trying to reverse this. So instead of writing for hours, I am going to write for four paragraphs.

Starting with this one. First of all, I believe that there is a strong bipartisan case for having more American brains in China, getting smarter on China, and building a body of expertise on China through the pretense of soft power diplomacy programs like Fulbright. This point has been well made by other Fulbright alumni so I won’t belabor it now (see here and here and here). Plus, to insert Sec. 3(i) in an Executive Order otherwise aimed at removing preferential economic terms with Hong Kong seems incoherent at best. At worst, it may have been the result of a certain vengeance. This was suggested to me by one senior Senate staffer, who in 2021 met with a group of us who were lobbying for the program’s reinstatement. Over the phone, this staffer suggested that this EO provision may have been inserted by someone who was bitter about not getting a Fulbright grant themselves.

After this phone call, I discovered that Matt Pottinger was the president’s Deputy National Security Advisor at the time the EO was published. Fluent in Mandarin, Pottinger has built much of his career around China expertise, and it’s reasonable to assume he would have been heavily involved in drafting this Executive Order. Pottinger’s resume does not include Fulbright. I cannot write any more along that line of reasoning without delving too deeply into conjecture, so I’ll leave it at that and you can make of it what you wish. Matt Pottinger is free to email me at jamescarrico@substack.com to share his perspective on why Fulbright programs were terminated in the P.R.C. (In advance of this post, I emailed him recently but have yet to receive any reply.) Incidentally, I was somewhat surprised to read his recent Free Press article which, while on the whole is a rather rambling, incoherent mess, did manage to squeak out an anti-isolationist position. Terminating soft power exchange programs is very much at odds with this foreign policy vision, and it would be interesting to hear his perspective on this apparent contradiction.

Thanks (I think) in part to our lobbying efforts, a bill was eventually sponsored in the House that aimed exactly to reverse the executive order. I was excited about this for a moment, until I realized the only sponsors are Democrats, so my confidence in this going anywhere is roughly zero. I believe the case for reinstatement can, should, and needs to be made on the right. Someday I will write more about this, now is not the time or place.

For now, the point is I never got to go to Hong Kong on the Fulbright grant to learn about Mei Wah Building. Thankfully, the State Department was miraculously flexible enough to provide for those with grants in Hong Kong and Mainland China to relocate rather than have the whole experience cancelled. My Hong Kong advisor had a contact in Singapore who graciously agreed to host me, so I went there as soon as the borders opened after the Covid shut-downs. I retooled my research interests as best I could. I learned a lot about Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, air-conditioned underwear, and many other things concerning tropical architecture and urbanism. I started this Substack (back when Substack was the wild west…no social-media-powered growth app like has now.) It was unquestionably a great and very horizon-broadening experience. I really have nothing to complain about, but the frank and honest truth is that I am still quietly upset that the same decision that prevented me from going to Hong Kong has damaged, not benefited American interests. That’s not how sacrifices are supposed to work. And based on the information I have been given, I have come to be of the opinion that the Hong Kong Fulbright was selfishly ripped away from me by a petty unelected bureaucrat incapable of such an accomplishment himself.

Pardon me, this is getting out of control. This is supposed to be about Beautiful Magnificent Building! But these things are important to me, so if this has come across as some wild unhinged tangent, allow me to first state my case that it is nothing of the sort. For as I state on this Substack’s “About” page:

I've long been interested in how non-design related fields and individuals influence things seemingly within architects' purview. Like Sir Winston Churchill, who famously said after the House of Commons was bombed: "We shape our buildings, thereafter they shape us." I continually question what this actually means, so it's become a prompt of sorts for this writing even though Almanac subject matter is not limited to buildings.

EO 13936 is connected to Mei Wah Building by proxy of my Fulbright proposal, so I’m simply doing what I set out to do here on The Architect’s Almanac. Now, I continue my Ode to Beautiful Magnificent Building.

Though what I can write about this magnificent edifice is brief, it still brings me a sense of closure on the whole ordeal. This post? A humble crumb of the twelve-course meal I would have made if I spent a year there meeting its inhabitants…documenting its mysteries…learning its stories. It has apartments available for rent on www.spacious.hk…I very well may have lived there, hopefully becoming a more beautiful magnificent person. Now it’s all now a dimming parade of imagined possibilities…

…this right here…this Ode to Beautiful Magnificent Building would have far outshined the most beautiful, magnificent essay I may have ever written. Alas, it’s now only a blog post. Ho-hum. One must move on, and with this ho-hum blog post, I think I will. It is not honorable to be bitter.

But the post goes on for now! Because just weeks ago, I found myself in Hong Kong on a layover with just enough time for a quick trek into the city. The idea dawned on me on the flight from Tapei to Hong Kong, and I calculated I could squeeze maybe 20 minutes walking around Mei Wah Building before hustling back to the airport for the 16-hour return flight home. I’d been to Hong Kong before but never seen Mei Wah Building in person, only photos and street views and Wikipedia articles on it. It made perfect sense: a quick trip to achieve inner-peace following the bitterness from the geopolitical crossfire turned career hit. My advisor has since forever left Hong Kong for America, so unfortunately there will be no indoor access or wise insights. Still, I’ve come to crave the feeling of finally seeing a place in person, after thoroughly exhausting its existence in every possible digital form. This alone would make the excursion worth it. Upon landing and storing my luggage, I made straight for the MRT which would bring me right into the city center.

On the strangely empty train into the city, quickly alternating scenes flashed by the characteristically warm and beautifully sunny day outside: vast industrial shipping ports, the outer New Territory “suburbs”, with their sky-high housing towers over bulky retail podiums, developed on the limited supply of flat land among the steep green hills of Canton. I reflected on what I remembered about my preliminary reading on Mei Wah Building. My initial focus in this particular address stemmed from a broader interest in a type of building Hong Kong has come to be known for: the composite building. A composite building is, in the words of University of Hong Kong Professor Eunice Seng, “a city within a building.” Unique to the extreme urban environment of Hong Kong, the composite building is a fascinating architectural type that is defined by the amalgamation of several functions traditionally housed in separate buildings: restaurants, cafes, chapels, offices, hotels, clinics, dormitories, apartments, community organizations and more fall under one roof, connected through passageways that function more like public streets than hallways. These hyperdense structures offer an intriguing design paradigm because of their material and spatial efficiency, as well as the unusual complexity of different kinds of uses in close proximity in a single building.

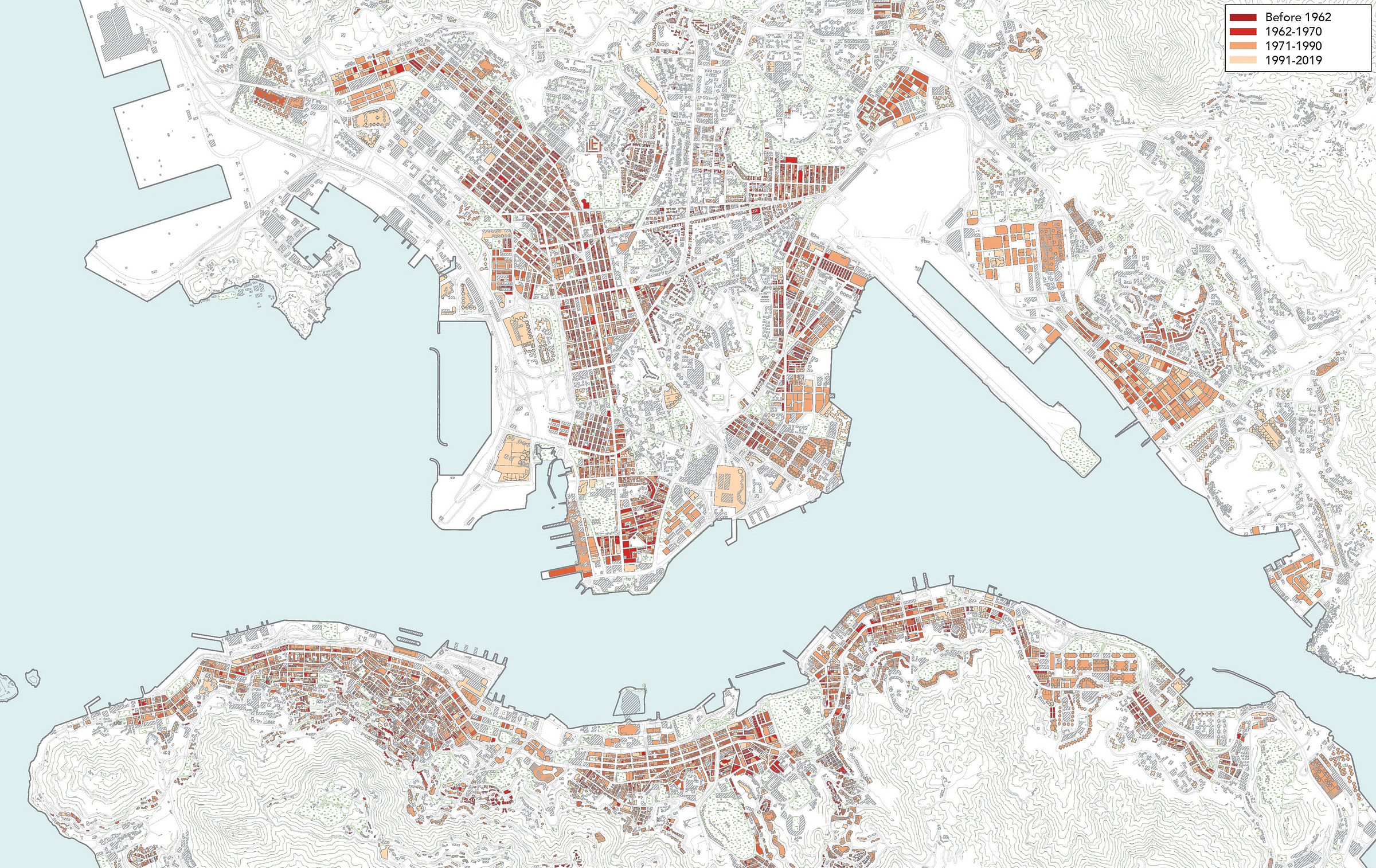

While mixed-use buildings are nothing new or by any means exclusive to Hong Kong, the term “composite building” came to be used both by scholars and even the planning arm of the Hong Kong Hong government to specifically refer to the ultra-dense, now rapidly aging concrete buildings originally built in the 50’s and 60’s. Due to their age, and originally intended 50-year lifespan, composite buildings are increasingly being torn down (or in one or two unfortunate cases, unexpectedly collapsing). Still, they define a significant portion of Hong Kong’s building stock today, an unmistakable part of its staggeringly dense, coarse city fabric in much of the Island and Kowloon Peninsula.

Arguably, composite buildings can be thought of as a kind of typological remnant of the truly spectacular infamous bulk of city known as Kowloon Walled City (KWC), the completely unregulated urban enclave with debatable sovereignty in central Kowloon. Reaching up to 14 stories and containing a shocking 30,000 people in a land area less than 7-acres, KWC was density and mixed-use maxxing to an unprecedented and unrepeated degree. Carved by a network of dismal alleyways, many less than 6’ wide with the light and air to show for it, the “City of Darkness” had no zoning, few police, and little enforcement of any construction or use regulation.

(It’s interesting in the context of this post that in 1992, architecture student Suenn Ho received a Fulbright research grant to do an architectural study on the Kowloon Walled City, which resulted in a small publication: Ho, Suenn. 1993. “An Architectural Study on the Kowloon Walled City : Preliminary Findings.” Hong Kong: Suenn Ho. Only a few dozen of these books were produced; some architecture schools have them. I have a copy, and it reveals a truly extraordinary creation.)

KWC was demolished in 1993 and has been replaced with a park (good for public safety, bad for urban history savants), but in some small way its spirit is present in the composite buildings that still stand today. In particular, buildings like Mei Wah Building also have a seemingly organic and varied distribution of interior uses. It’s not shy about it either, as one of the first things I noticed when I approached the building for the first time was the giant Chinese characters that advertise various uses throughout different floors:

Mei Wah Building is unapologetically utilitarian in its visual character as an architectural form totally shaped by the city. This plays out in four dimensions, beginning with the two-dimensional site plan, which demonstrates how the building is basically an extrusion of its parcel. After barely tangentially connecting, Wan Chai Road peels left and Johnston Road peels right. Mei Wah Building’s parcel is formed in the split with its most distinctive acute corner condition on the east side.

Architecturally, this “point” of the building is resolved by rounding off the corner in plan, making a terrific focal point for living rooms defined by a long, faceted curve of comfortably sized operable metal windows. Many of the individual windowpanes appear to be original, as indicated by the decorative iron grills so characteristic of mid-century Hong Kong buildings on floors 3, 4, 6, 8, and 11. These inset grills may be the only trace of ornament on the exterior of the building, other than the signage. Looking through these windows from the inside, one gets a spectacular double canyon view down Johnston Road and Wan Chai Road from this lofted and advantageous urban perch.

The rounded corner is also where the third dimension factors into the form-making of Mei Wah Building. To understand this, an abbreviated history of Hong Kong zoning is in order. Between 1955 and 1966, Hong Kong operated under a zoning policy whereby the sizes of buildings were regulated volumetrically. To maintain adequate light and air at street level, setbacks were required for buildings above a certain height, and the setbacks increased the taller a building was. So, taller buildings built in this period have a characteristically “stepped” appearance, similar to many skyscrapers in Manhattan (New York City has a similar setback-based zoning policy.) But in extra-dense 20th-century Hong Kong, even this was not restrictive enough to adequately deal with overcrowding. In the early 60’s, the government took steps to implement a new zoning mechanism that instead shaped buildings by site coverage requirements. That resulted in the “pencil tower” type buildings that so define Hong Kong today, but it also spurred a flurry of building permit applications that aimed to acquire approval before the newer, more restrictive requirements went into effect. A building boom commenced, resulting in the construction of thousands of composite buildings built under the volumetric zoning regime. Completed in 1963, Mei Wah Building is an exemplar of this post-setback-zoning but pre-site-coverage-zoning era. At 14 stories tall, it’s just tall enough to reach the setback zone, as can be seen by looking carefully at the top two levels.

Another feature of its rounded corner is that it doesn’t go all the way to the ground, but instead starts at the more residential heavy third floor, thereby creating a small canopy that begins at the “point” of the building and continues along the entire length of facade on Johnston Road. This is a common strategy to sneak in more building mass in Hong Kong, a city-state where the average family of three lives in apartments smaller than 500 square feet. In the pervasive shove for more space, the area traditionally used for balconies or terraces in more spacious urban locales simply ends up becoming part of the interior. From the street, the resulting cantilever creates a kind of skinny architectural umbrella. This peculiar condition is everywhere in Hong Kong...walk around the city a bit and once you see it, you’ll never stop noticing it.

Last is the impact of other kinds of changing regulations over time, the fourth dimension’s impact on Mei Wai Building. As Ho Yin Lee and Lynne DeStefano note in their introductory essay for Michael Wolf’s Corner Houses, a photo compilation of composite buildings:

As Hong Kong intensified its light manufacturing industries in the 1950s and the 1960s, upper-floor tenants of composite buildings exploited the increased commercial opportunities by operating small businesses and unlicensed cottage industries. A typical multi-storey composite building of this period could contain a variety of commercial outlets, from home-businesses, such as trading companies, traditional Chinese medical practices, private schools and fortune tellers, to cottage industries that produced garment parts, toys and plastic flowers. As Hong Kong has become more mature and organized in its land-use policy and urban planning, it is hard to imagine the chaotic diversity of commercial activities that once existed in composite buildings.

Mei Wah building is somewhat unique in that its multi-functional nature isn’t extinct yet, though one assumes it’s a far cry from the cacophony of uses it hosted decades ago. The exterior of the building has certainly evolved along with Hong Kong’s regulatory push in recent decades to remove cantilevered neon signs, under the auspices of structural safety concerns. Today, one proud lonely, magnificent holdout remains: the lovely neon green tea leaf sign for Ki Chan Tea Company.

I will now pivot to present tense to make the following experience read more vividly.

I look at my watch. Eight minutes left. On a sudden flash of inspiration, perhaps a longing for some shred of research credibility to this absurd excursion, I spy a nearby public library. Snapping a few photos of Beautiful Magnificent Building in context along the way, I jog through crowded narrow rush hour streets to get there.

Library…library…a security guard directs me to a weathered metallic chrome elevator, “5th floor”.

I walk in, elevated heart rate, ask the quizzical librarian if they might have any documents related to a nearby building…I gesture behind me, foolishly hoping she’ll immediately understand my predicament and exclaim “MEI WAH BUILDING! Yes, there’s a whole section on it right behind you…take some with you!”

She instead blinks once behind her N95 mask before politely directing me one floor down, “there’s a section on Wan Chai neighborhood history downstairs, you can look there.”

…Four minutes…

The Wan Chai section is a tall but narrow shelf — fitting for Hong Kong, I think to myself — chock full of books, most of which are written in traditional Chinese. I browse, hurriedly. Nothing sticks out, but then again, what could I possibly absorb in a few minutes? I learned well in Singapore: resource diving takes ages, and when done well, usually several phone calls. There’s nothing to do. Time is up. I have some phone photos, and a nice memory of a brief walk around a striking building on a warm and sunny afternoon in an enchanting land far away, punctuated by a bewildered but friendly librarian.

Our flight leaves Hong Kong as scheduled; I made it back to the airport in time just fine. It’s night now. We fly right over the urban center of Hong Kong, its distinct development profile with undeveloped hillsides in the black of night now in highest contrast with the sparkling metropolis. So ends my engagement with Beautiful Magnificent Building, down there somewhere in the twinkle between Mount Cameron and Victoria Harbor. It slowly drifts away, on this trip but forever, too, becoming only a brief memory of a place briefly seen but not known.

Thoughts, questions, comments, reactions? Reply to this email or send me a note: jamescarrico@substack.com. Responses get addressed in the next post.

All text and images ©James Carrico unless otherwise cited.

Selected additional reading on composite buildings and related topics in Hong Kong:

Lee, Ho-yin, Lynne D DiStefano, Chi-pong Lai, AnnaMarie Bliss, and Dak Kopec. 2020. “Hong Kong’s Early Composite Building: Appraising the Social Value and Place Meaning of a Distinctive Living Urban Heritage.” In Place Meaning and Attachment, 1st ed., 171–81. United Kingdom: Routledge.

Seng, Eunice. “The City in a Building: A Brief Social History of Urban Hong Kong.” Studii de Istoria Și Teoria Arhitecturii, vol. 2017, no. 5, 2017, pp. 81–98 Link

Wolf, Michael, et al. Hong Kong Corner Houses. Hong Kong University Press, 2011.

Yip, Ngai Ming, and Ray Forrest. 2002. “Property Owning Democracies? Home Owner Corporations in Hong Kong.” Housing Studies 17 (5): 703–20.