Retrofitting a Nation (2/2)

Enclosing Singaporean public space part 2: public housing elevators

Read Retrofitting a Nation (part 1/2) here.

Never in short supply of idealism, the United States has borne witness to some seriously (suspiciously?) lofty pretensions when it comes to skip-stop elevators. It could never just be a device to lift people up and down with the inconvenient side effect of overshooting the intended destination by a floor or three. No, skip-stop elevators, and the adjacent and corresponding corridors served, have a recurring presence in casual utopian visions of urban living. They would create social “neighborhoods”1 within a building, not mere hallways but “interior streets…promoting social interaction and community sense.”2 And lest one is left with the impression that skip-stop technology ended with the 20th century and the death of the “abstract architecture” of the “high rise apartment”,3 simply fast forward a few decades. Post millennium, it’s hankering for a comeback under the auspices of health and wellness. (One truly cannot make this stuff up.) The new trend is perhaps most blatantly epitomized by the “Burn Calories Not Electricity” meme-like poster apparent in such significant documents as New York City’s 2050 Strategic Plan, where a chapter on “Active Design Guidelines” bluntly recommends “installing skip-stop elevators where appropriate”.4

Critics of this millennial-oriented fad — perhaps most pointedly represented by those with legitimate accessibility needs — may cite Singapore’s more pragmatic mindset. Once again, this Substack will shift its attention there for most of the remainder of this working essay.

Dominated by the People’s Action Party (PAP) since independence, the Singaporean government through the Housing Development Board (HDB) has consistently provided copious communal facilities alongside high-density public housing. But skip-stop elevators and their associated corridors emblematic of most pre-1990 buildings were, for their part, not formally considered part of this social regimen. According to an exhaustive dissertation on public housing in mid-century Singapore, externalized HDB corridors were largely intended to solve utilitarian concerns of “access, surveillance, and frontage”, and were “sized for circulation and not for dwelling or intermingling”.5

To the extent that the corridors took on a social character, it follows that this was due to things like the humble but humanist practices of breeze-seeking middle class residents: doors left open, flower pots (tolerated in moderation) scattered, et. cetera.6 Barring a sermon from the Housing & Development Board, one is left to conclude that whatever glimmers of social life the corridors did happen to facilitate emerged in spite of the planning intentions behind the corridors, not because of them.

But there is more to the story lurking within these elements of tropical architecture.

First, a brief recap. As explained in part 1/2 of this essay, the 2001 Lift Upgrading Program (LUP) saw the systematic upgrade and addition of elevators in over 5,000 buildings. With the looming prospect of an increasingly comfort-keen but also increasingly aging, staircase-resistant society, the swift construction of the elevator retrofits was equally robustly pragmatic in spirit as the original, urgently constructed skip-stop elevator configured buildings.

(One could also speculate that the viral demolition of Pruitt Igoe in St. Louis, along with its infamously ill-maintained elevators, imposed something of a scarlet letter on the skip-stop strategy. Rationally or not, this may have accelerated the appetite for upgraded elevators that served all floors, especially in places like highly connected, highly visible, and highly globalized Singapore.)

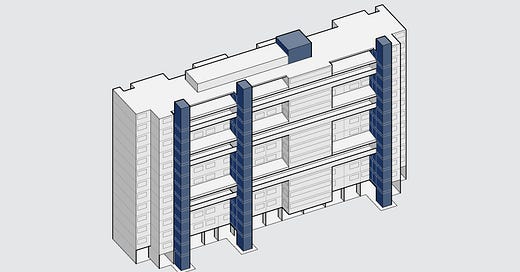

Now proudly foregrounding its three new elevator towers, Block 411 (discussed & pictured in last week’s post) is exemplary of the retrofit condition now ubiquitous in Singapore. But perhaps more interesting than its Lego-like architecture are campaign declarations made by the People’s Action Party in the years running up to the formal unveiling of LUP. Ever attentive to seemingly minute details of ordinary life, the PAP made it known that housing upgrades were on the ballot in the 1997 general election.

To be fair, the following paragraphs should be presented with a slight hedge. The degree to which elevator upgrades specifically — elevators were/are one example of many types of housing upgrading programs — were operating under the below mentioned “votes-for-upgrading” framework is not entirely clear.7 Following legislation passed in 2005, LUP upgrades were newly allowed to be financed by local town councils.8 Since those are occasionally run by opposition parties, this would presumably give opposition districts the authority to implement retrofits on their own, with PAP’s blessing not required.9 Still, elevator upgrades were implemented in other programs besides LUP and may have been under the national purview, as LUP itself was from its inception in 2001 until 2005. The unsatisfying acknowledgement of this working essay is that there may be more questions than answers when it comes to these matters.

Anyway, as far as HDB upgrades were concerned more broadly, Southeast Asia expert James Chin summarized one peculiar aspect of the ‘97 election (emphasis mine):

The tactic adopted to counter the by-election strategy was the ‘votes-for-upgrading’ strategy, pitting the PAP’s ward improvement plans against what the opposition had to offer. Voters were told that their vote was tied directly to their eligibility for the Housing and Development Board (HDB) estate upgrading programmes. Under these programmes the government pays 80 per cent of the cost of modernizing a flat, about S$45,000 each. This effectively muted the opposition’s argument that voting for them would have little or no consequence, as the PAP was already in power. There was only one criterion for qualification for the upgrading programme - victory for the PAP candidate in that constituency.10

This is also alluded to in several newspaper articles from the time, for example:

When Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong said on Tuesday he would say something interesting during his visit to Potong Pasir which would make Opposition MP Chiam See Tong jump, eyebrows were raised.

They were raised even more when he said yesterday that he would offer HDB upgrading to Potong Pasir residents “even if Chiam See Tong wins”.

But there is one condition – the precinct that wants upgrading has to register at least a 50 per cent vote for PAP candidate, Mr Sitoh Yih Pin.11

And finally, researchers at the National University of Singapore recently published a paper that investigates qualitative outcomes of these policies. While they don’t draw from LUP data, their work provides high quality evidence that links districts with higher PAP support with expedited upgrades in three other HDB-related programs:

We find that, on average, housing blocks in constituencies held by the ruling party have a higher probability of being chosen for upgrading than do those in constituencies held by the opposition parties, and the pattern is more significant in the election season—defined as one year before an election—than in other periods.12

However delayed or accelerated the retrofits might have been, by now (2022) the vast majority of older HDB flats have upgraded elevators. As mentioned in part 1, the Ministry of National Development recently wrote that only some 150 buildings are left unupgraded due to technical constraints.13 A recent visit to a pair of them lends anecdotal support to that reasoning.

An odd, elongated, very pink, and very-out-of-place-in-their-surroundings pair of buildings stand unupgraded at 3 & 4 Queens Road.14 They’re snug against a major road on one side, a less major road on the other, and a major MRT line skewers the ground somewhere near the foundations. On top of that, both are especially long, and the units are arranged in a stacked configuration (like Block 411 - see plan diagrams in part 1). It would take a ridiculous amount of elevators to serve every unit. 22 to be exact, including four replacements for the skip-stop ones there now.15

Clearly, retrofitting buildings under these physical circumstances would be understandably outlandish to the point of being absurd. Regardless of Queens Road’s politics, 22 elevators may just be too many for the PAP to muster here. As for the other 148? The Housing and Development Board has not graced the public with the list.

(Perhaps if they did, planners in New York City could study them as high-quality, real world case studies of occupant fitness.)

Until they do, one can reflect on a statement made by a well known architectural writer who declared the “death” of Modern Architecture to be the moment a well known housing project with skip-stop elevators was demolished in St. Louis. Curiously, the skip-stop elevator itself lives on here and there. Helping some burn one or two calories here, getting HDB dwellers of the 150 hold-outs back home (awkwardly) there. If Modern Architecture is dead, its pesky elevators “live” on, like zombies. Brace yourself if they’re headed for a corridor near you. Because maybe America was right. There is a lot more to skip-stop elevators than efficient conveyance.

Enjoy some photos of shared corridors in one of the remaining skip-stop-elevator appointed buildings in Singapore, posted below the footnotes.

"Slum Surgery in St. Louis”, Architectural Forum 94 (April 1951) pp. 128-136

Ysniguchi, Jan Tokuichi. May 1979. “VERTICAL NEIGHBORHOODS:A RESIDENTIAL HIGH-RISE DESIGN EXPLORATION. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (link)

Housing and Planning References;1979 ASI 5002-2;HUD-319-(nos.)-ASI. 1979.

“ACTIVE DESIGN GUIDELINES: ACTIVE PROMOTING PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND HEALTH IN DESIGN. 2010. City of New York. (link)

Seng, Eunice. “Habitation and the Invention of a Nation, Singapore 1936-1979.” Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Columbia University, 2014.

The flower pots curiously reaching a crescendo near the left-open doors…one speculates the two are casually related.

Upgrades included more than elevators, but elevators would have been a major part of any upgrades, especially at this time. For examples of other upgrading programs, see the Main Upgrading Program (MUP), the Home Improvement Program (HIP), the Interim Upgrading Program (IUP), the Neighborhood Renewal Program (NRP).

Republic of Singapore. Government Gazette. Acts Supplement (2005, August 19). Town Councils (Amendment) Act, 2005 (Act 23 of 2005, pp. 901–917). Singapore: Singapore National Printers. Call no.: RSING 348.5957 SGGAS; Republic of Singapore. Government Gazette. Subsidiary Legislation Supplement. (2005, August 19). Town Councils (Amendment) Act (Commencement) Notification 2005 (S541/2005, pp. 2458–2459). Call no.: RSING 348.5957 SGGSLS.

See page 8 of the “Housing Externalities and Expectation Channel” article linked below.

Chin, James. 1997. “Anti-Christian Chinese Chauvinists and HDB Upgrades: The 1997 Singapore General Election.” South East Asia Research 5 (3): 227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967828X9700500302.

Rahim, Zakaria Abdul. “PMs new carrot”. TODAY. November 1, 2001. Page 2. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Page/today20011101-2.1.2?ST=1&AT=advanced&K=Goh%20Chok%20Tong%20HDB&KA=Goh%20Chok%20Tong%20HDB&DF=14%2F10%2F2001&DT=10%2F11%2F2001&NPT=&L=&CTA=&QT=goh,chok,tong,hdb&oref=article (Accessed May 23, 2022)

Diao, Mi, Tien Foo Sing, and Xiaoyu Zhang. n.d. “Housing Externalities and Expectation Channel: A Quasi-Experiment Using Public Housing Upgrading Programs.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3891016.

Incidentally, this would not be the first article to identify this otherwise innocuous building: see the Rice Media article “Lift-less in Singapore” for a charmingly humanist account of the tribulations of a few residents in that HDB flat.